When Johannes Foersom applied to the School of Arts and Crafts, as it was called then, applicants had to be trained in a craft in order to qualify. Thus, the architects who would be designing buildings actually knew how to make a timber construction, and designers had hands-on experience with various materials before they embarked on their studies. The Royal Danish Academy, as it is now called, became an academic institution in 2010, and over the past 12 years, its approach has become increasingly theoretical. According to the students, this means that the practical experience and knowledge they gain in the workshops are not given sufficient priority.

These voices of frustration and dissatisfaction resonate with Johannes Foersom, who was a student himself when the large student rebellion of 1969 was raging. Foersom does not recall a similar focus on political issues at the school; instead, he remembers the content of the projects they were assigned. According to Foersom, they were traditional and old-fashioned and involved making painstaking measurements of a chair and learning to draw it by hand – complete with shadows. Foersom’s generation found it more relevant to make a difference and engage in projects that improved people’s everyday life, such as creating innovative urban spaces, playgrounds and courtyards in the city’s densely populated areas.

Progressive rector

According to the established designer, this was actually accomplished. The students were heard. Perhaps due to the appointment of a new, progressive rector, Ole Gjerløv-Knudsen, who was open to contemporary ideas and recognized the need to shake things up.

‘Our school had new teachers come in who responded to some of the needs we presented in the subject area councils. Going from a sense of reverence towards the institution itself and the tradition embedded in the teaching and subject areas, we were able to change the content and bring in new types of teachers and guest teachers thanks to the rector’s understanding and willingness to listen. He also provided grants so we could examine things for ourselves. We went on a trip to visit workshops abroad and see their approaches, such as the artists’ collective workshop in Stockholm or the production collective Kullerup Tøj (Kullerup Clothing). When I became a teacher myself, in the 1980s, we engaged with environment, sustainability and life cycle analyses, which were emerging issues at the time and in demand among the students.’– Johannes Foersom

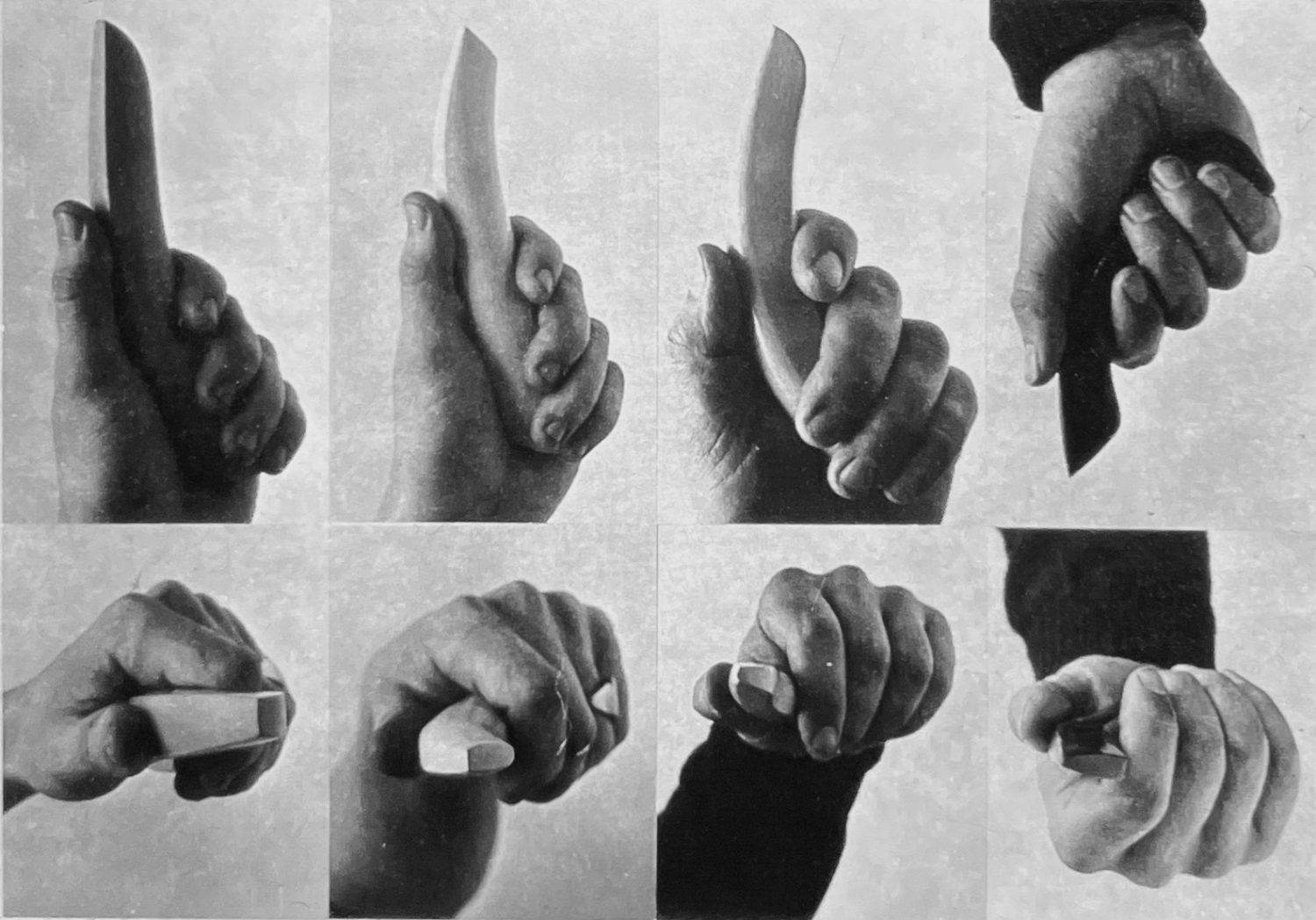

The topics that were put on the agenda during Johannes Foersom’s student days had a lasting impact on his generation of design professionals. From the late 1970s and 1980s, the studio that he founded with fellow furniture designer Peter Hiort-Lorenzen began to design products for people with physical impairments, including anything from walking sticks, cutting boards and lighting to furniture and other items that were beautiful and could be used by everyone.

The academic challenge

Today, the main focus in the field of design is on climate challenges and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, and according to Foersom, that is how it must be. However, he also sees this as an opportunity and a gift, as it offers designers a chance to shape a new aesthetic. A new approach to form and design, as materials play a major role in determining the resulting design expression, and industry ends up overtaking the once progressive design schools, because money talks, and the intrinsic logic of the market forces outpace the less agile and more rigid education system.

‘New players are entering the scene due to current cycles in the marketplace, which is turning designers into spectators. The waste industry is developing in leaps and bounds, and new materials are being created. So far, they have been ugly, but they are being made because there is gold hiding in all that waste. That is a feature designers need to deal with. If teak or oak is sold out, you have to make do with coffee grounds or turnip mash. There are also lots of surplus materials and natural materials that we have to learn to use in new ways. That is an inescapable condition in design today, and if you don’t take an interest in materials, or if you’re not able to find inspiration in these materials, it’s a problem,’ he explains, arguing that the new materials will only come to play a more determining role in design processes as the planet’s resources become increasingly scarce.

Foersom also thinks that the schools are too old-fashioned in their approach to research.

‘The academization of the school seems to somehow stand in the way of the realization that research can be based on materials and hands-on processes in the workshop rather than being exclusively about books. The government ministries are applying an outdated mindset that is completely useless in the context of creative professions – from their hiring practices to the types of people the bring in from the theoretical university setting. I would suggest involving a much more diverse field of actors in the selection of teachers and project partners and making room for a wider range of practical knowledge about such topics as materials, experiments and industrial processes. I think there are too many PhDs sitting in their offices and working on things that are probably great and boost the school’s reputation, but you need to include people who work with these things in the real world. There are lots of people from industry who have in-depth experience with these issues – in construction, in the furniture industry and, not least, in the fashion and textile industry.’

Design is dynamic

Johannes Foersom is sympathetic to the students and their calls for a deeper engagement with materials and more workshop hours. Today, materials are a complex and ever-changing concept. While earlier designers were used to relating strictly to wood, steel, glass, clay and textile, today, the range of materials has undergone explosive growth to include entirely new types that behave very differently and function across the field in unprecedented ways.

Foersom also recalls that since the programme only lasted three years, the students were very aware of the need to delve in, making the most of it while it lasted. This active approach to studying and the possibilities of a new era – and the fact that the students felt seen and heard – helped energize the entire institution.

‘The leadership of the school were themselves interested in the changes that were unfolding. Design is a dynamic concept, after all, and if it doesn’t reflect its time, it becomes pointless. If an educational institution fails to keep up with the times, it becomes irrelevant, and the education it offers is worthless. In a school, you need people who have their finger on the pulse. And when you receive inputs, as a design student, you need to render these inputs tangible and manageable. Otherwise, it risks becoming too theoretical, lacking materiality and a connection to real life. Instead, relating it to topics that are rooted in a material realm makes it meaningful.’

Generational gap?

Today, the dream of being an independent cabinetmaker and having one’s own studio is alive and well. The romantic dream of producing handmade furniture is a contemporary trend, according to Foersom. This is in part because it aligns with the notion of sustainability but also because it represents an escape from the complicated world we live in. In the workshop you do not have to deal with the complicated questions of necessity in the same ultimate way that is required if you manufacture furniture or other products on an industrial scale. After all, the world does not actually need another object or another piece of furniture. These considerations are only going to become more urgent. They were not an issue at the time of Foersom’s graduation, when the main issue was to design furniture everyone could afford.

‘Today, many are questioning whether it is even acceptable to buy a T-shirt, because the production causes so much waste and pollution. That is an impossible debate. I think that’s why many young people like to work hands-on with wood, which offers a direct response, unrelated to the considerations of whether making something is a good idea or not. I think we have moved past the stage when design was all about trends. That wave, when HAY, Muuto, Normann Copenhagen and others were like home interior fashion houses and were embraced with enthusiasm by many young people, is ending, as the issue of necessity and resources is growing more urgent.’

He also recalls that the concepts of collectivity and quality were hot topics when he was a student. They were endlessly poring over those ideas, he says. Today’s students have a global outlook and planetary awareness, as the key focus now is on all of humanity. Something needs to change. In Foersom’s opinion, how to achieve this change is up for debate … However, he is convinced that the young generation is very aware of what they are getting into when they choose to study design. Their goal is not to create decorative items or frills, they want to make a difference:

‘In that sense, design is pushing to regulate the world in a way that is proper and decent. And the concept of quality is going to take on new dimensions. Traditionally, we have based the notion of quality on the aesthetic virtues, which date from a different era and which were all about the material – how does it appear, does it possess intrinsic quality, it is beautifully processed and so forth? Now, the focus is more on the resources that the material consumes or what it leaves behind in the total sum of footprints on the planet. However, I hope that we don’t abandon the aesthetic dimension. If we devote resources to designing something, it really should possess a value that it not only measured in physical terms but also on a psychological scale. There should be a connection between physical and aesthetic sustainability. The whole process of recycling materials also represents a consumption of resources, so the sustainability aspect of a long lifespan is not insignificant,’ says the established designer, furniture maker and teacher, whose opinions and perspectives illustrate that history tends to repeat itself – but always in new ways.

Bio

Johannes Foersom completed his training as a furniture maker in 1964-69 and graduated as a designer from the furniture line of the School of Arts and Crafts in 1972.

In addition, he taught in the textile programme at the School of Decorative Art, as it was then called, in 1972–80 and in the furniture programme in 1980–95.

In 1979 he established the design studio Foersom Hiort-Lorenzen together with furniture designer Peter Hiort-Lorenzen in Nyhavn, Copenhagen.

Here, the design duo has been creating award-winning design and furniture projects for 40 years.

Theme: Student rebellion

Formkraft gives the floor to both students and institutions and examines contemporary educational opportunities for craft artists and designers.

Follow along from November 2022 – January 2023 when Formkraft takes stock of the design education in Denmark.