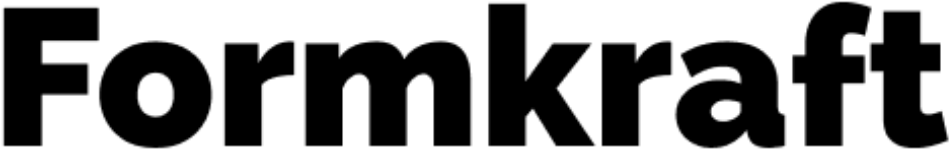

Photo: Vibeke Riisberg, Tætte Vaser (1993/94)

Conference means bringing together, but in fact, only two of the speakers were physically present at the University of Southern Denmark for the conference Kunsthåndvæk i en digital tid (Craft in a Digital Age) on 20 January, while almost everybody else joined the event digitally from locations in several countries.

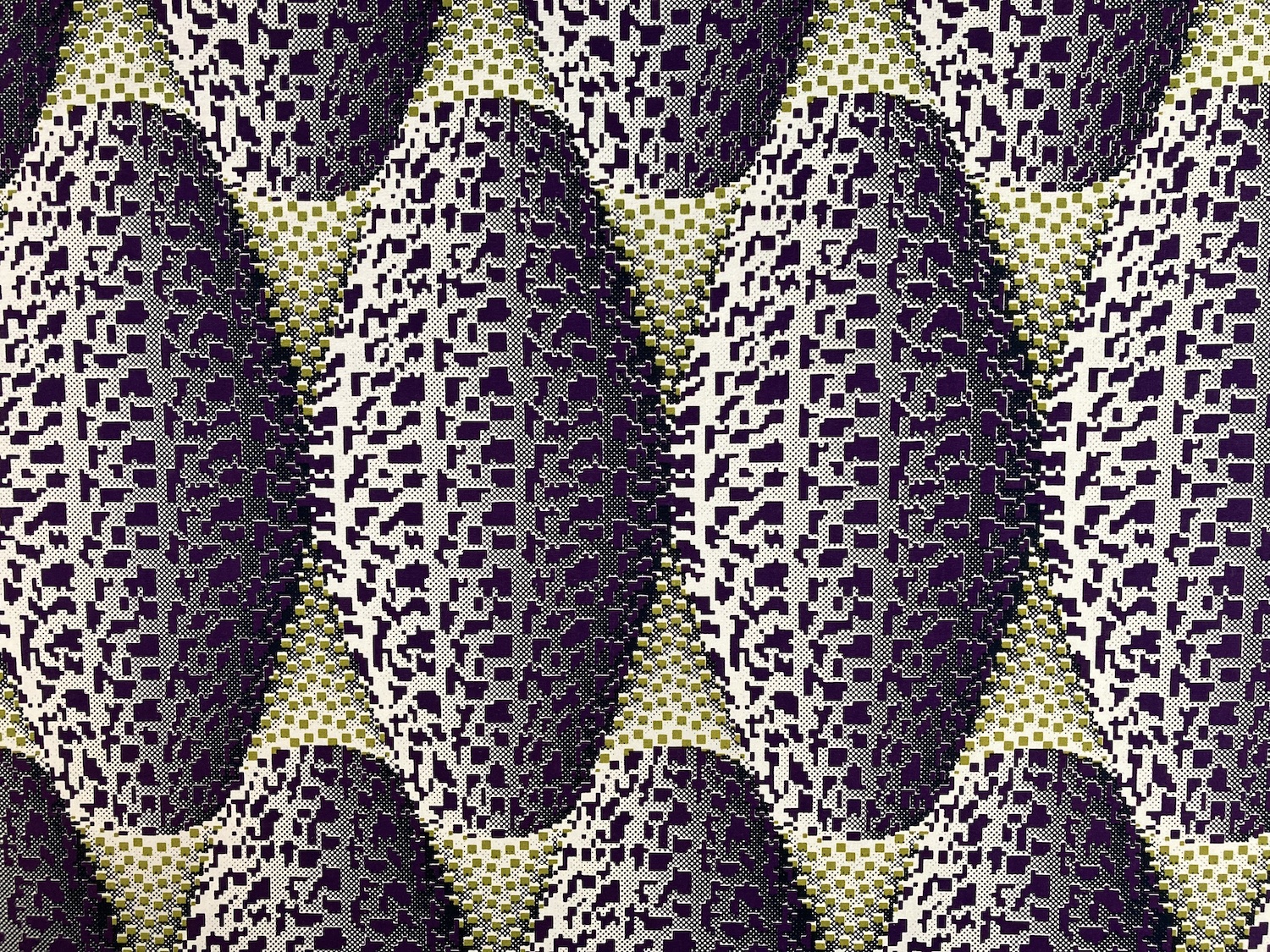

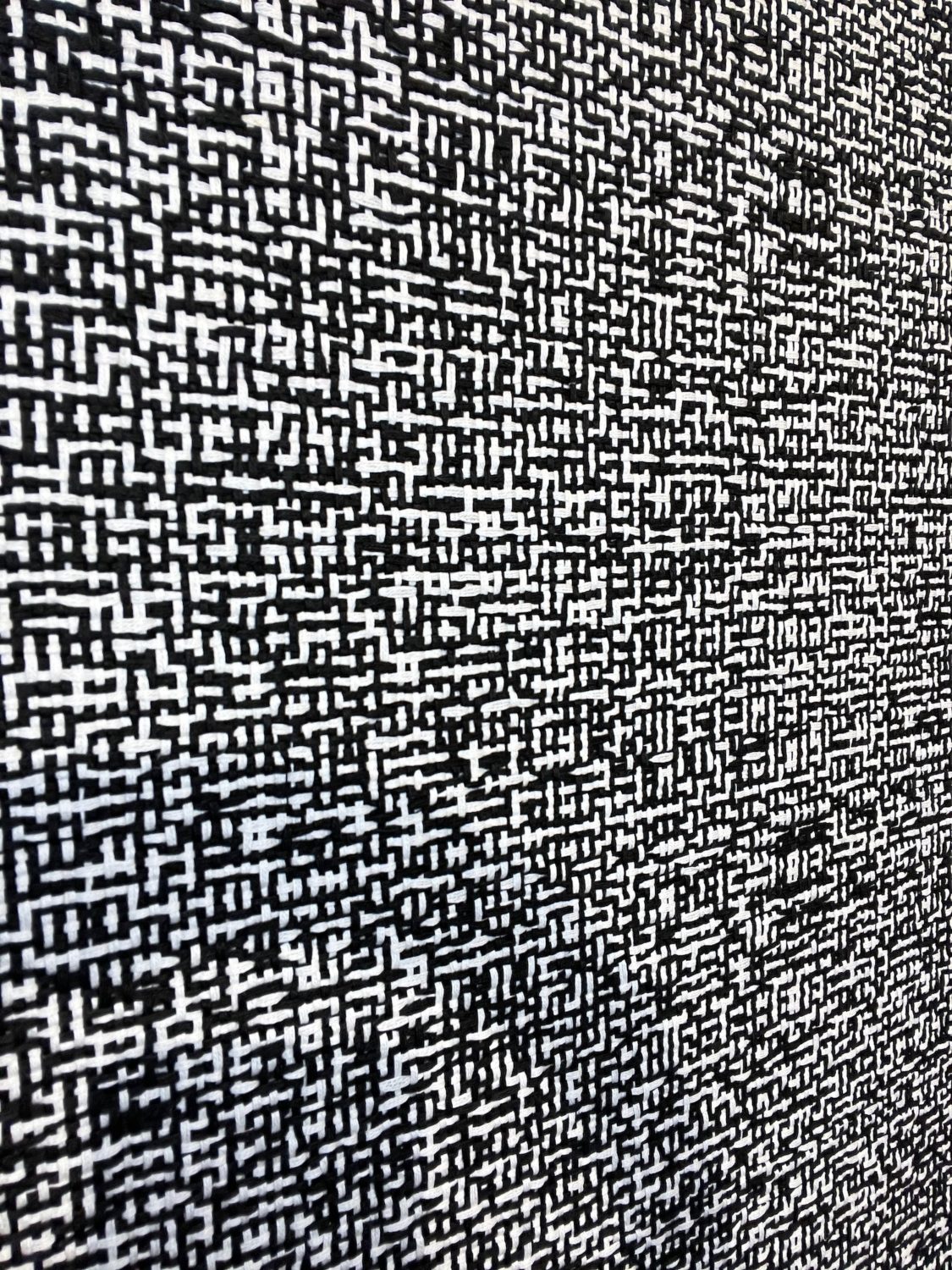

This ironic point reflects a core aspect of the theme: nothing is more sensuous and tangible than crafts. That quality requires materials, people and methods to come together physically in the workshop, and yet, the field cannot escape the digital conditions of our current time.

Everyone is bound up in electronic networks, including contemporary craft makers, and new digital possibilities have long since entered the field in the form of new technological methods, from digital weaving to 3D printing.

Speakers

Keyspeaker: Tim Ingold, Emeritus Professor, University of Aberdeen (UK)

Speakers:

Cilla Robach, Head of design collection, National Museum, Stockholm

Ingrid Halland, architecture and design historian

Anne Fabricius Møller, fabric printer and textile designer

Panel debate:

Morten Løbner Espersen, ceramicist

Vibeke Riisberg, textile designer, PhD, Design School Kolding

Rebecca Uth, industriel designer

Morten Riis, Deputy Mayor and Chairman of Maker’s Island, Bornholm

Anders V. Munch, PhD design history

Naturally, this alters the maker’s reality, just as the status of the field has changed profoundly over the past century. After the radical developments around 1900, when many expected arts and crafts to inspire and elevate industry, the many disciplines of craft slipped into the margins of production and were increasingly seen not just as a luxury but even as an irrational and unjustifiably time-consuming pursuit, as described by Cilla Robach, one of the speakers, who participated from Stockholm via Zoom.

Today, some even find the time-consuming craft process provoking, not only because it makes things expensive but simply because it is seen as unreasonable to choose to devote so much time to it. Robach observed that this response is not commonly heard in relation to other pursuits, such as art or music.

She referred to the Swedish professor of economics Mats Alvesson’s study of ‘the triumph of emptiness’ in modern life: since the abstract content of our work often fails to offer a real sense of reward or satisfaction, we compensate by seeking a quick ‘kick’ of happiness from shopping, buying mass-produced objects of unknown origin.

White withdrawal

Emptiness was also a theme in Ingrid Halland’s study of how the colour white spread on walls in domestic and public interiors from 1930 on, surrounding the people in the room with a clinically calm surface that was so inconspicuous it almost seemed to vanish. The formula for cheap, non-toxic white paint was developed in Norway during the 1920s, based on locally available titanium dioxide, and soon, ‘titanium white’ spread to all modern interiors.

The white walls eliminate the ‘noise’ of the colours, wallpapers, curtains and tapestries that used to cover the walls, Halland explained. Instead, the white surface creates an unhomely atmosphere, because it is so inconspicuous that it becomes virtually invisible.

Her analysis invited relevant reflections on why it was so important for people in modernity and late modernity to create these oddly frictionless spaces dominated by whiteness – from white walls to immaculate white sofa sets and white kitchens, disrupted only by so-called neutral colours, if at all. What sort of resetting is it that this seeks – a refuge from the ever-accelerating pace and stress of the world? A white canvas that life itself may, cautiously, fill out?

This emptiness is related to the lack of texture: the less texture, the less noise and the less friction – but also the less stimulation and the fewer places for our senses to find rest. Smooth home, smooth consumption, smooth work – all these friction-less and slightly impersonal domains may be regarded as important aspects of the extreme acceleration that is characterizing late modern living. Ever more work, ever more consumption, ever more production, every more mobility.

More friction

Is the controversial pursuit of craft, as Cilla Robach described it, part of the antidote – can the objects resulting from complex, time-consuming labour reintroduce friction into our life? Development has introduced a huge distance to things – we do not know their origin, composition or history, and they exist in a space that is deliberately staged to be as blank as possible, with noiseless white surfaces. Makers place objects centre stage and allow them to be time-consuming, ‘difficult’ and noticeable, to take up room and engage their environment in dialogue. In this digital age, is it now time to refocus on the hand behind it all?

This perspective was voiced by several participants during this half-day virtual conference, and the panel debate in particular focused on the need for a sensory upgrade of modern life and improved material literacy. ‘We need to restore the sensuousness of things, so we can meet them with appreciation and respect,’ said Morten Riis, chair of Maker’s Island on the island of Bornholm. Designer Rebekka Uth highlighted the craft field as a space for experimentation, invention and new ideas.

Vibeke Riisberg from Design School Kolding pointed to the possibility of reducing the rapid pace of production by digital means, for example through production on demand, and Anders V. Munch underscored the need for transparency in production in a world of ‘black box’ factories.

The more consumers know about the complex processes of production, the better they understand their actual value, as several participants pointed out, and in this regard too, the path goes through the tangible world: workshop, methods, materials, the hand behind it all.

A learning rope

In fact, we should see craft as an alternative learning approach and a way to reintroduce creative and artistic sensibilities into education overall, according to the keynote speaker of the event, the British anthropologist Tim Ingold. Academic learning has become a practice where knowledge is efficiently transmitted, in measured portions, from teacher to student. This stands in contrast to the hands-on learning in the workshop, ‘the messy theatres of practice’, as Ingold put it, with grandfatherly charm.

We no longer see the copying of a technique as innovation, but it is, he argued, pointing to the reciprocal nature of the traditional interaction between master and apprentice, as the student reinvents the technique in her own way, and the master in turn learns from the student.

While academic education today is based on a notion of generations as separate layers, where the legacy of each generation is passed on to the next, Ingold proposes viewing the learning process as a rope wound up of fibres, where the generations learn, develop and continuously renew approaches in an infinite and overlapping winding process. It is in this interaction with things that Ingold sees the true potential, as students learn to attend and answer to the things and beings in the world. This open and responsive engagement with the life of things breeds responsibility or, as Ingold calls it, response-ability: the capacity to respond and answer to things and the world around us.

We might choose to see all education from this perspective, he suggested: as an obligation to give back to the world rather than as a means simply to lift students up to well-paid, high-status jobs. This would also enable us to re-establish the connection between education and the democratic community that was severed in the slickness of late modernity. He described it as baroque that the academic world been so removed from lived life that we refer solely to academically generated knowledge – since knowledge, of course, also arises in the workshop and in our day-to-day exploration of the world. ‘I think it is the mission of art, craft and design to lead a revolution in the whole way we think about education and its role in society,’ argued the thoughtful professor emeritus, who also reminded us that the Latin word for ‘educate’, educare, comes from ex-ducare: to lead the student out into the world. A world whose major crises today are closely associated with overproduction and overconsumption.

This is not a revolution we can leave solely up to the craft makers, Morten Riis argued in the subsequent panel debate. It is not sufficient to place them alone in charge of sensuousness. ‘Craft is driving a radical development to assign creativity a bigger role in education,’ says Vibeke Riisberg. And this education does not begin in design schools or universities – the sense of materials and their origins and ongoing life must be developed much earlier. However, perhaps makers can and should be part of the vanguard of such a revolution?

The conference

The conference Crafts in a digital age was streamed from the University of Southern Denmark in Kolding on 20 January 2022.

Through exchange of knowledge and debate, the goal was to explore how crafts and design can give shape to all areas of our society.

The conference had about 800 participants from all over the Nordic region.

Watch the recording of the conference here

Theme

What part do craft artists and designers play in the streamed society when tactile experiences become fewer and the physical interaction is taken over by streaming, social media and online shopping? Formkraft dives into the theme: Crafts in a digital Age