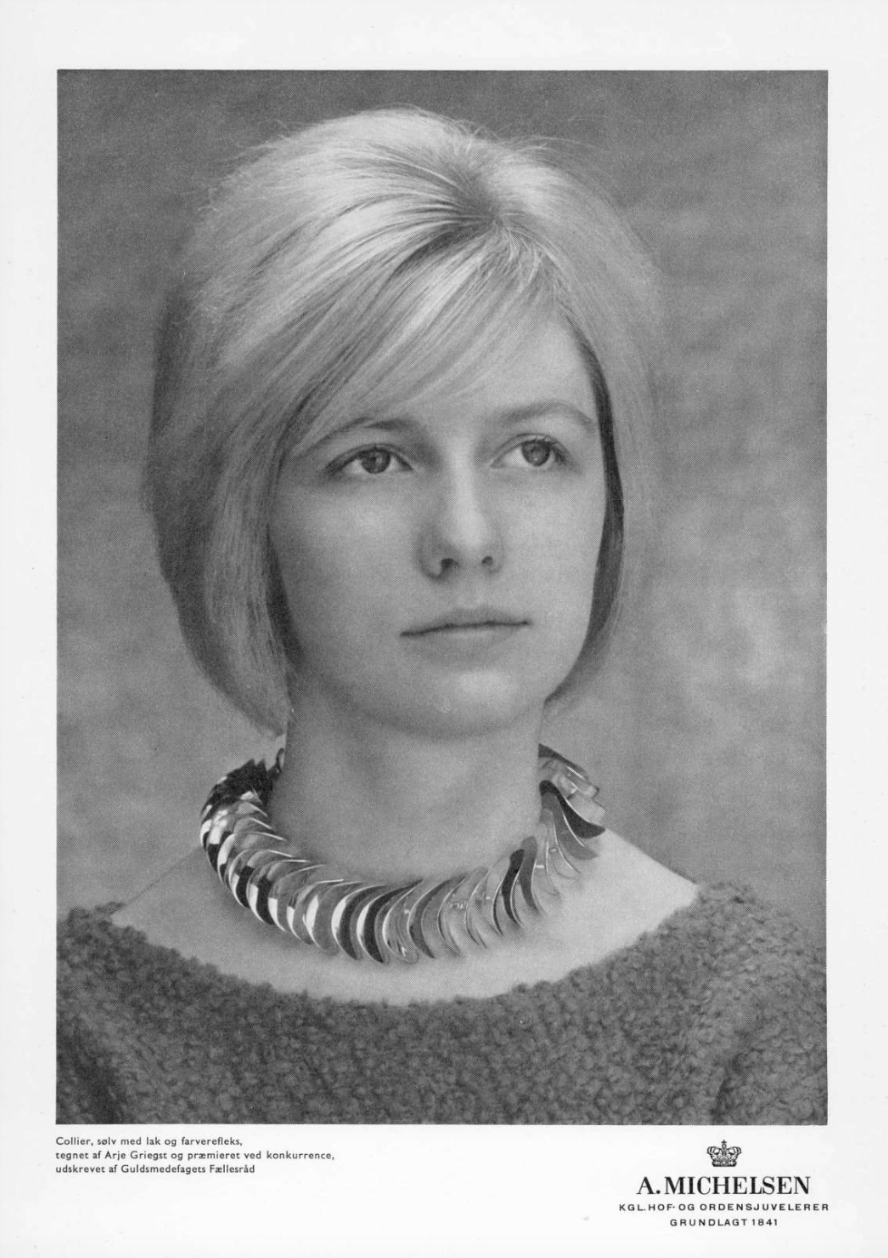

In the last century, Danish jewellery art flourished with new forms reduced to the most minimal and sensual. Looking back at old photos, it is quite impressive that a large part of the middle class was willing to wear new types of jewellery. Modernist jewellery art often turned towards more humble and everyday materials and motifs – the simple nature, glass, steel, plastic – and in that way broke with the traditional status hierarchy of jewellery.

But when mass production and mass consumption took off in the 1970s and also made jewellery into fast fashion, the surest profit lay in delivering cheap versions of the ‘fine’ and status-giving. Everyone wants gold, diamonds, champagne, cashmere and brand-new homes that look as if they are untouched by human hand. And preferably cheaply. But that gold and diamonds are so coveted that they retain their value even in the worst crises is obviously a social construction and not a natural law. Once, it was lace, spices, and scarlet clothes that were the bomb. And it is also not a natural law that beauty and jewellery can only be produced from the currently most expensive materials. Aesthetics itself is taken hostage by status battles. Often, luxury, including expensive jewellery, is despairingly predictable. There is a need for a rebellion against the entrenched ideas of what is beautiful and luxurious. Sublime, even. And here the jewellery is central.

For what is a piece of jewellery at all? What is it made of? How should it be worn? To bring out the beauty in new materials is an invitation to aestheticize new fields of life, and with the right approach, jewellery can indeed be an entry for many to the sustainable thought of buying fewer, but more beautiful things. And to dare to take on a new expression.

The conditions for Danish jewellery art, however, are not the easiest. The Institute for Precious Metals was closed in 2016, and at the Design School in Kolding, jewellery design has tellingly been absorbed by the ‘accessories’ area. The nearest education in jewellery art and design is as far away as Munich. There is a need for rallying points and a common movement that can animate new talents, and the Danish Art Foundation is trying for the first time in decades with a competition.

In a globalized world, it is doubtful whether one can once again create an explicitly Danish jewelry art – and essentially indifferent. More interesting is whether across national boundaries one can revitalize jewelry and with new materials and forms achieve something that is so sublime, stimulating and special that it is worth continuing with.

Theme: Contemporary Jewellery Art

Can Danish jewellery art renew itself when the artistic education has been shut down and the field does not have a dedicated professional museum in Denmark?

What traditions and stories does Danish jewellery art build on? How does the industry relate to contemporary demands for sustainability and new consumer patterns? Does jewellery still have a justification in a world of abundance, climate anxiety, and malaise?

Much suggests that Danish jewellery art finds its own ways in spite of everything.

From September 28-30, the Copenhagen Goldsmiths’ Guild invites you for the third time to a full program during ‘City of Jewellery’ in Copenhagen.

Formkraft focuses on Danish jewellery art anno 2023. Articles under this theme are published in the period August-September-October.