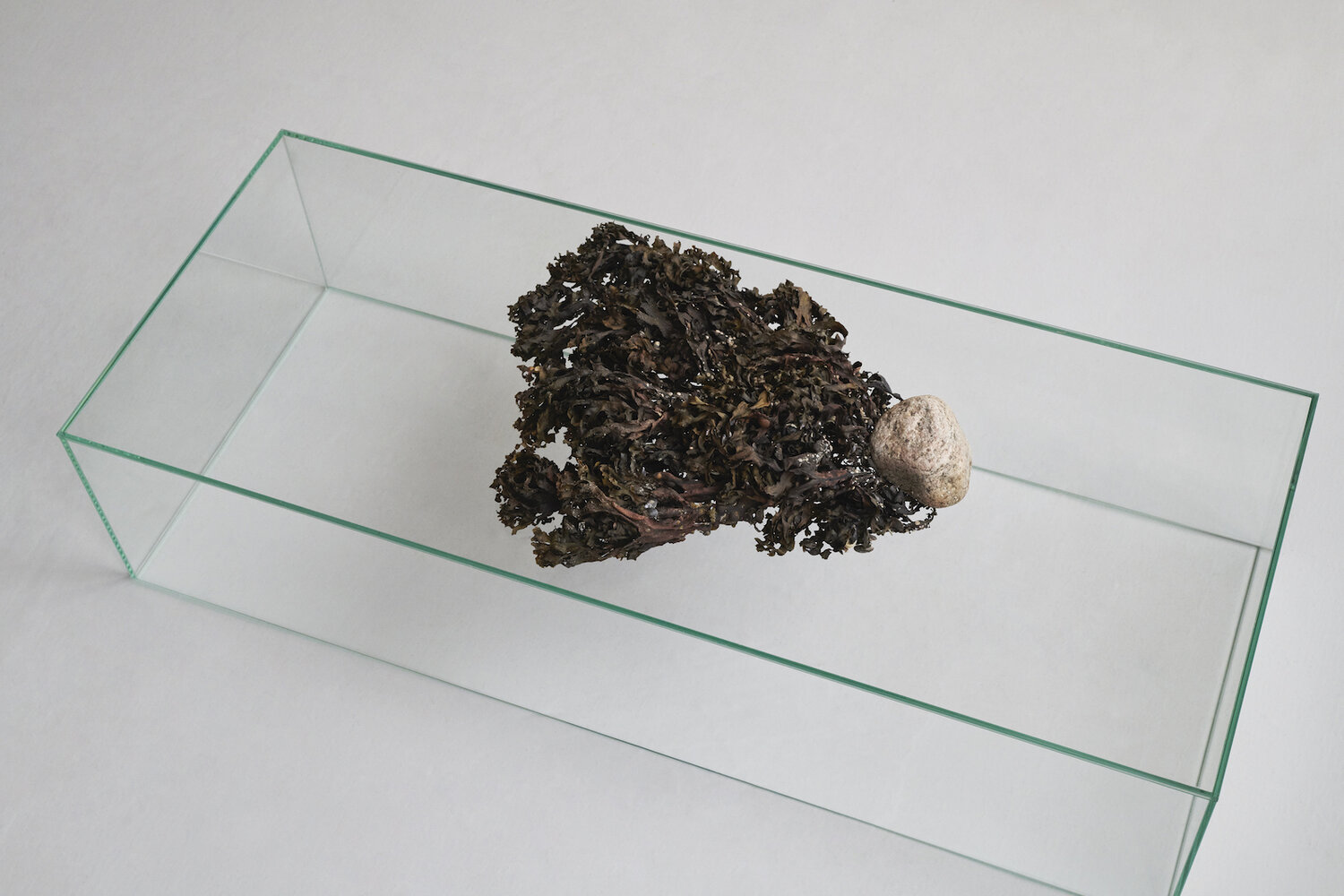

Photo: Maria Viftrup. Geofuturistisk Eksperiment. Photographer Martin Kristensen

A practical point of departure

Like most designers and makers I insist that the world needs sensuous qualities and sensibilities. Our body is not just a vehicle for our head. We grasp our world through the way we thrive in and feel welcomed by our environment and by sensing the materials around us. Thus, design can be seen as solutions in material form attempting to meet contemporary needs and yearnings.

I trained at a polytechnic college in a time when our output or ‘artwork’ was expected to speak for itself, so we did not put a priority on accompanying verbal descriptions. That is quite different now that the design programmes have university status, and practice, theory, method and communication go hand in hand. I am writing from the perspective of my own experience as a practitioner and a teacher over the past 15 years, as this development has unfolded. In this process, I have followed outstanding future practitioners within my own field and observed how they constantly challenge the field through new modes of expression and meaning. Thus, my point of view is not that of a researcher but of a passionate practitioner with first-hand knowledge about the wide range of contributions we can make.

Helle Graabæk

Helle Graabæk graduated from the School of Arts and Crafts in Kolding in 1992, specializing in printed textiles. Helle has an independent practice as a craft maker and designer and has worked with Kvadrat and Le Klint. In 2000 she was awarded the Danish Arts Foundation’s three-year working grant. For the past 15 years, she has worked as a teaching associate professor and manager of the textile programme at Design School Kolding (DSKD).

The competencies of makers and designers – thinking through making

Professor and philosopher Donald Schön, who studied the nature of practice, viewed design as a conversation with what he calls the situation, a negotiation in the creative process with the materials afforded by the situation. In this conversation, the situation will ask, and the practitioner will answer. Thus, a good design process will always be reflective

‘When someone reflects-in-action, he becomes a researcher in the practice context. He is not dependent on the categories of established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case. (…)He does not keep means and ends separate, but defines them interactively as he frames a problematic situation.’ (Schön, 1983, p. 68)

As designers and makers, we are trained to search for answers in an iterative process, as we experiment with the materials, techniques and methods of our field in a continuous effort to analyse, evaluate and choose the possibilities that prove to have the greatest potential in relation to what we wish to bring into the world. The magic of the creative process, as so aptly described by Schön, is that the situation answers and shows us new possibilities that we could not have imagined from the outset.

We develop frameworks and intentions for our investigative processes, and these boundaries set us free to experiment by defining a specific focus.

We are experts in the methods, materials, techniques and tools of our field and seek to challenge them through experiments so that they can show us new possibilities that may also challenge contemporary industry and production.

We seek to improve our understanding of the situation and the context in which our output has to make sense. To this end, we need to understand and empathize with the user and carefully consider the experience we want the user to have in the sensuous encounter with our products.

We develop prototypes and use them as tools for dialogue and a visual ‘language’ through which we can test, communicate with ourselves and others and receive feedback and new insights.

We strive to come up with answers to the challenges of our time and to create humane, meaningful products, experiences and solutions in response to the shortcomings we identify, for example the lack of sensuous qualities and sensibilities in our environment.

Design and crafts can give shape to visions and ideas of the good life in our time and in the future from the perspective of a NOW moment. That is exactly what William Morris, Bauhaus and Dansk Design, among others, did by taking a critical stance to their own time. Fortunately, there appears to be a growing focus on the significance of quality craftsmanship with the establishment of projects such as the European Homo Faber Guide, EU’s Craft Hub and EU’s New European Bauhaus vision. The latter is summarized as follows:

The New European Bauhaus initiative calls on all of us to imagine and build together a sustainable and inclusive future that is beautiful for our eyes, minds, and souls. Beautiful are the places, practices, and experiences that are:

- Enriching, inspired by art and culture, responding to needs beyond functionality.

- Sustainable, in harmony with nature, the environment, and our planet.

- Inclusive, encouraging a dialogue across cultures, disciplines, genders and ages.

One of the challenges to our ability as designers to gain real influence on our present and future is that we need to develop and engage in new ways and train our ability to communicate what we do and the contributions we can make. Our practice is based on the maker’s and designer’s knowledge of quality and durability and the new methods we develop through deep professional knowledge and continuous reflection on how we can contribute.

We need to demonstrate how the ideas of the good life that the EU’s New Bauhaus vision suggests can find new form and generate meaning and value beyond the purely material level.

We should no longer just let our output speak for itself as we did when I was trained.

We can learn to communicate from the heart of the situation, in the engine room where the magic happens, using the platforms available to us and making them our own as invitations to understand what quality is and what it can be. Fortunately, many of our colleagues have come a long way in this regard, and we can learn from them.

One example is designer Sara Martinsen, whose digital encyclopaedia Phytophilia provides knowledge about how plants and vegetable fibres can be used for aesthetic and practical purposes in design and architecture.

Designskolen Kolding

At Designskolen Kolding DSKD, the bachelor’s programme offers focused three-year programmes in fashion, accessory, industrial, communication and textile design.

The master’s programmes cover three themes, all focused on contemporary challenges.

New design solutions are developed through project-based courses:

PLANET: focused on the lack of sustainable, holistic solutions in society.

PEOPLE: focused on growing inequality and the lack of inclusion of various groups in society.

PLAY: focused on the lack of creativity and playful approaches in society.

Digital natives

The students accepted into our textile education programmes today are mainly motivated by a passion for and curiosity towards the craft of their field. Craft is best learned through an introduction to the analogue textile tools and the techniques of weaving, printing and knitting. The slowness of these techniques helps the students understand and grasp through their body and hands. This gives them a sense of how they can create sensuous tactile experiences for others in the interplay of materials, colours, construction and aesthetics.

The level of complexity increases through the progression of the programme: digital textile tools are introduced after the students have developed an understanding through analogue approaches. We introduce and work with digital tools, different contexts such as space and body, design methods, theory, user insight and collaboration projects with companies. The digital tools enable the students to approach and grasp craftsmanship and production in new ways. More knowledge on this subject: Pixels, algorithms and crafts by Anne Louise Bang

The students we encounter today are so-called digital natives: born after 1990, they have grown up with the Internet, smartphones and social media as a natural aspect of life, almost an extension of themselves. They are used to sharing everyday situations visually on social media, being in continuous contact with the outside world and receiving immediate feedback. Many of them incorporate this form of engagement in their projects, including shooting films to present things that need to be experienced in motion and stills for close-ups and detailed views. They do not distinguish between analogue and digital techniques and methods in their work, since to them, these are all just tools. Most importantly, however: they have a conscious ambition of driving positive change through their work.

Designer, maker and artist Maria Viftrup is a good example of this new generation of makers and designers who challenge the field’s boundaries, sensuous qualities, sustainability, interaction and communication and interaction in their work. She insists on focused presence, reflection and relevance by exploring how we can co-exist. Her works can be seen as a response to Marianne Krogh’s encyclopaedia Connectedness from 2021. In a mention of the encyclopaedia the Danish Arts Foundation wrote:

‘In light of the current challenges to humanity it is essential that we examine what binds us together and search for ways to strengthen the threads that run through all living things – the intimate, fundamental connection between human beings and nature.’

How do you instil your own sense of wonder in someone else?

Maria Viftrup works with a wide and diverse range of materials. She is curious about their origin, distribution and presence in our contemporary world and how she can invite others to share her curiosity by staging encounters between materials and audience. As a textile designer, she is trained in constructing textile materials. Through her studies she has become a passionate collector of materials which she organizes into archive form. Her approach is the opposite of the traditional textile trade: she dismantles the construction of found textiles and products and reshapes them into new forms and structures in collaboration with her audience.

Through this, she invites them into a sensuous encounter with the materials. In many of her workshops and exhibitions she challenges the traditional ‘Do not touch’ rule, because it reduces the tactile, physical engagement and disengages people’s sense of touch and their grasp of material distinctions. Maria’s motivation is to contribute to a more sustainable future and approach to materials.

She encourages people to wonder and reflect on the disposable culture she grew up with and seeks to change attitudes by staging sensuous interactions. She gives the participants the experience of contributing to the production of aesthetic objects and works of art. Most importantly, she sows a seed of curiosity about our material world and our use of materials and encourages the participants to wonder and ask questions of their own. All change occurs through deep, physical awareness. That is the only way we can change our attitudes and, perhaps, our behaviour.

Three projects – three different approaches to the process

Below, I present three of Maria Viftrup’s projects, which illustrate her approach to colours and materials and her aesthetic expression. As a designer she adopts a variety of positions in the individual artwork: from creating the overall aesthetic expression of the piece to acting as a facilitator, co-creating with and through others based on a theme she wishes to explore.

In Material Pigment Archives, Maria Viftrup examines the relationship between materials, colour and waste that she collects in waste bins around the city. By granulating the found materials she has created 208 pigments, offering the viewer a physical colour experience by transforming objects that have been stripped of value and restaging them in an aesthetic exhibition format. The presentation is a rhythmic, lab-like format where the simplicity of the system brings out the diversity of colours and materials in a new way.

Temporary Archive of Objects Ecosystems, 2018

In the workshop and exhibition project Temporary Archive of Objects Ecosystems from 2018 she examines ‘how we create and consume materials and products’. The workshop participants construct objects, creating a total of 1,500 sculptural forms over 25 hours, which become the exhibition. Maria has selected fibre materials and cast bioplastic objects using found items as moulds.

In the workshop the participants go through three phases:

- A sensory experience of the material and the joy of touching and co-creating

- Reflection on their engagement with the materials that surround them in their everyday lives

- Exchange and dialogue about contemporary and former systems of production and consumer culture

Geofuturistic Experiment was presented at Klimafolkemødet (People’s Climate Summit) in 2020. At this event, Maria asked the participants, ‘What powers are going to shape the (geological) foundation of the future?’

This question was debated during the five hours that the participants spent creating the piece and completing the experiment. Maria’s role as designer was to define the concept and the framework, turn the granulated items into materials and invite a critical dialogue about the future. The framework she created enabled the participants to engage as co-creators of a piece of high aesthetic quality. Through the colourful layers the participants also articulated their own reflections on the question and left additional traces by writing these reflections on the glass front of the piece in white ink.

To borrow Schön’s terminology, Maria clearly engages as a researcher and reflects on and in her own practice. She has rendered herself independent from traditional techniques, asks critical questions of the situation and does not set apart the means from the ends but defines them interactively.

She shares her knowledge from a profound grasp of her craft and discovery of her own identity as a maker, and she is able to see, hear and feel how she can contribute to today’s challenges from her own perspective. She achieves this by turning her own experiences into an opportunity for non-practitioners to similarly grasp and reflect on our material world and how things are made.

How can crafts and design drive change?

In the introduction to his 2013 book Making, anthropologist Tim Ingold writes:

‘The only way one can really know things – that is, from the very inside of one’s being – is through a process of self-discovery. To know things you have to grow into them, and let them grow in you, so that they become part of who you are. (…) It is, in short, by watching, listening and feeling – by paying attention to what the world has to tell us – that we can learn.’

For anyone who works with crafts and design, I think there is resonance and truth in Ingold’s words. We experience things physically, from within the situation, and have spent endless time growing into our field by seeing, hearing and feeling what the ‘world’ and our experiments can tell us. Through this, we develop ourselves and our field. A maker’s or designer’s products, created through lengthy practice, can be seen as physical manifestations of the inner development of dialogue we have had with our material and the world. As such, they contribute our intention and contribution.

In a world of endless Black Fridays and a society with growing loneliness, anxiety, depression and stress, one way many of our fellow citizens appear to be able to find some brief satisfaction is an overconsumption of clothes and lifestyle products. This seems to offer the only way to shape one’s identity.

We have an opportunity to rekindle others’ awareness of quality, spark reflection and raise questions about how we can invite and involve others through our work as makers and designers. We can also raise questions about how we can invite traditional sensuous experiences and interactions with our products and artworks – and whether we sometimes maintain our distance by only appealing to the sense of vision when we present and display our works. Might we learn from applied art, where the encounter with a beautiful cup, for example, calls for us to touch the object and grasp the weight of the material and the way it rests in the hand?

Like Maria Viftrup we can choose to ask new questions about what we take for granted, asking ourselves how we can contribute and involve others in new ways. We can drive meaningful change from the bottom up if we see it as part of our work to rekindle others’ appreciation of quality. Through this we can teach users to reflect on and understand what quality products are and the processes involved in quality craftsmanship. As designers we can establish new professional forums for the exchange of knowledge and experiment with finding new ways to communicate our insights: how intention, materials, process and quality through form can become physical statements about how we view the world and what we wish to change.

There is a clear interest in things created by hand that emphasize slowness and sensuous qualities.

The young generations are taking online ‘knitting tutorials’ because they did not learn the skill from previous generations. Repair cafés pop up in European cities, and ceramics courses in Denmark are fully signed virtually as soon as they are announced. Socioeconomic initiatives, such as SheWorks and I Tråd med Verden,aim to integrate women from minority ethnic backgrounds using textile crafts as a common language, generating meaning and offering an opportunity to contribute by creating beautiful products.

We can reflect on and ask new questions of our practice.

We can use social media to communicate and promote our work – a way to gain influence and generate awareness of quality.

We can consider how each of us can rekindle others’ awareness of craftsmanship and quality and thus how meaningful and rewarding a creative process is.

We can try to articulate and ask questions about our own practice and the knowledge we acquire from within the process, because we are the experts on what we create. Or we can remain in the shadows of ‘tacit knowledge’, leaving the responsibility for communication to others.

We can strive to drive a velvet revolution from the bottom up and from inside our practice, because we have so much to contribute!

Faktaboks

References:

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Temple Smith.

Krogh, M. (Ed.) (2020). Connectedness: An incomplete encyclopedia of the Anthropocene. Strandberg Publishing.

Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. Routledge.

Theme

Which opportunities and consequences does the digitalization of society have for our material understanding? Crafts in a digital age

More knowledge in the archive

Search the archive for more knowledge