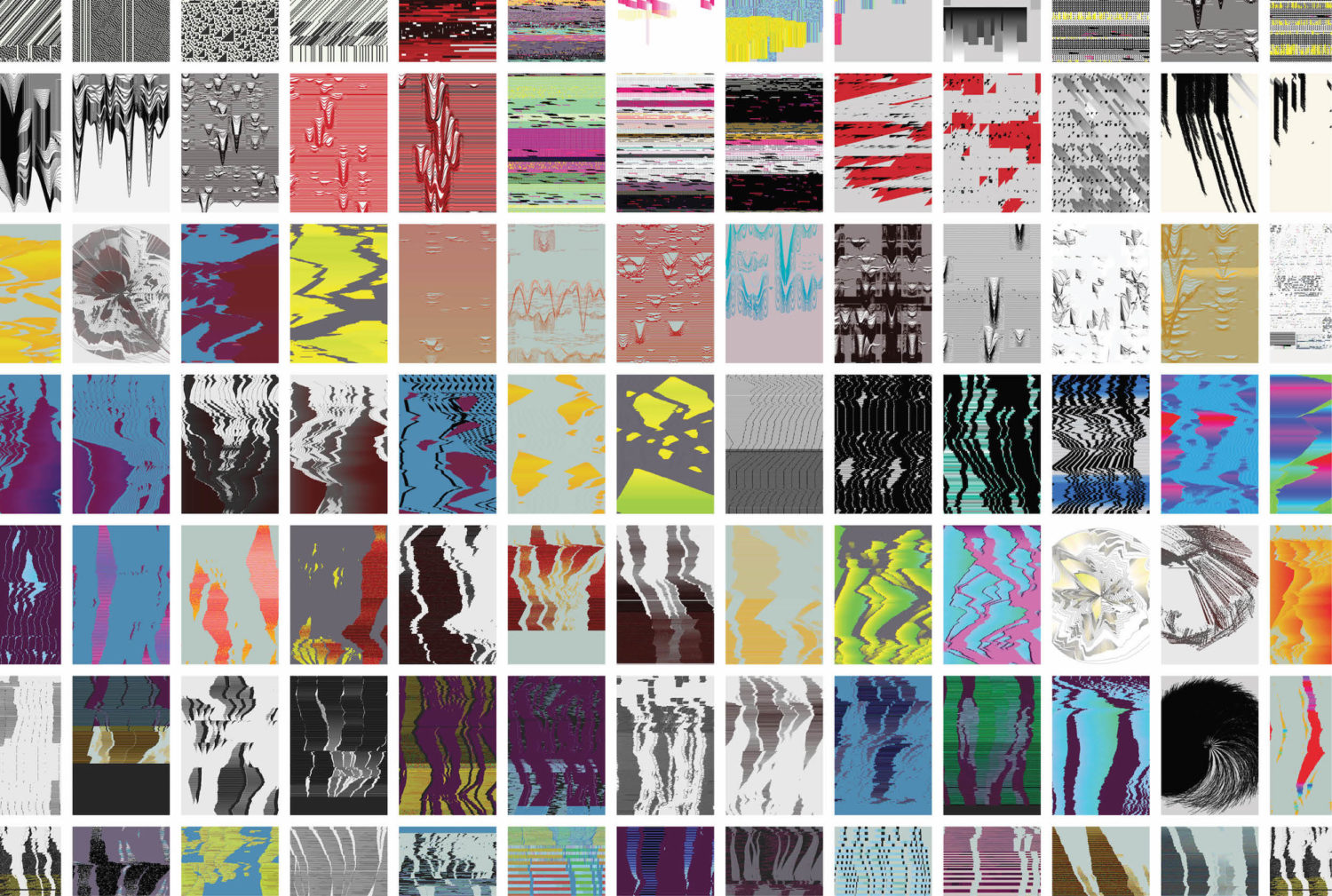

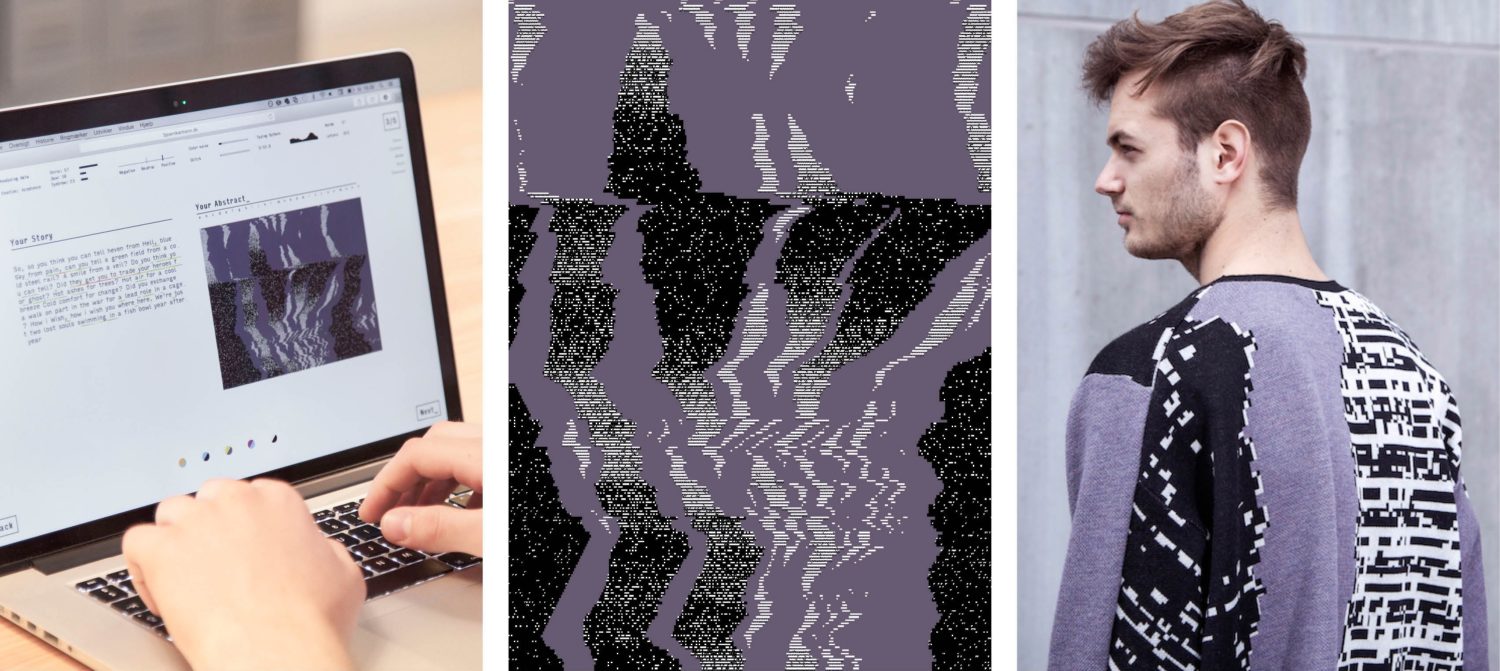

Photo: Abstract_ by Bjørn Karmann, interaktionsdesigner, Julie Helles Eriksen, beklædningsdesigner og Kristine Boesen, tekstildesigner

– Anni Albers

Now, why would I open an essay about craft and digitization with a quotation by the Bauhaus weaver and textile designer Anni Albers? The Danish encyclopaedia Den Store Danske defines craft as a symbiosis of art and technique, a practice that involves the shaping of both expression and materials in which the process itself is key and fully controlled by the maker.

In this essay I offer some examples of the influence of digital technology on the making of craft objects, the maker’s engagement with the materials and the craft process. My focus is on the current millennium and includes the role educational institutions have played in this development. Before we begin, let me point out that diving into this topic is a bit of a journey, with countless possible paths. Thus, the essay is merely a sample of a much bigger story, and it is impossible to include all the many individuals who have contributed to the digital development of the field.

I have chosen examples from weaving and ceramics, two areas that, with support from the educational programmes, have embraced the digital tools, made them available, included them in development efforts, challenged them and refined them while never losing sight of the craft itself in relation to the maker’s engagement with the material, the skilled craftsmanship and the artistic expression.

A turning point

When I began my studies in the textile design line at the School of Arts and Crafts in Kolding (now Design School Kolding) in 1989, digital technology and tools played only a minor role. E-mail, mobile telephones and the Internet were unknown, and although the workshops were full of technological devices and tools, they were mainly analogue and mechanical. I quickly chose to focus on weaving, and thinking back, the workshop did have a computer we could use to generate weave designs in a simple but efficient weaving program. Specifically, we were ‘spared’ the task of drawing weave designs by hand, while our work with and at the loom was the same as ever.

In the weaving hall, there was a single loom with electronic shaft control, where the weave design could be transferred directly to the loom. When I moved on to the advanced level in 1992, I remember that in the Department of Unique Design, we spent quite a bit of time on the purchase of two computers to be shared by the whole class, while we threw glances at the students in the Department of Visual Communication, who greedily explored the digital realm with one computer each.

In 1994–2001 I was away from the educational field. When I returned – initially as a guest teacher and later in a permanent position – a minor revolution had occurred. Electronic shaft control was now commonplace in the weaving studio, and the digital Single Thread Control jacquard loom had emerged. The latter let us control every single warp thread and thus allowed a new approach to free pattern design. To me, the digital tools became a turning point that enabled a more intuitive approach to weaving in unique works, design tasks and teaching. It became a new craft journey.

When the 3D printer met the clay

Both printing on two-dimensional surfaces and printing three-dimensional objects have changed radically with the development and spread of digital tools. Generally, since the turn of the millennium, the 3D printer has gone from being a costly and complicated high-tech tool to being affordable and fairly simple to use. As a result, many design schools have invested in workshops with a selection of different 3D printers. The small prototype printers using PLA with a low melting point are particularly popular, but printers capable of printing other types of plastic, metal, composites and clay have also found their way into the workshops.

For makers and designers who are used to working with 3D design programs, 3D printers offer an obvious way to produce both prototypes and finished objects. A fresh example from January 2022 is the newly graduated furniture designer Mathias Falkenstrøm, who takes part in the Danish TV programme ‘Danmarks næste klassiker’ (Denmark’s Next Design Classic). In the show he uses his own 3D printer to produce prototypes created in a 3D design program

I am curious about the impact of 3D printing on the traditional craft discipline of ceramics. In 2006, when the ceramic artist Flemming Tvede Hansen initiated his PhD project Material-driven 3D digital form giving at The Danish Design School (now the Royal Danish Academy), access to 3D printers in educational institutions was still a novelty, the machines were costly, and plastic was the main printing material.

In a conversation with Martin Bodilsen Kaldahl in the Kunstuff journal, among other topics Flemming Tvede Hansen mentions the difference between using the computer to visualize ideas versus focusing on the possibilities the digital tools offer as independent generators of form, as he did in his PhD project. He points to the possibility of working not just with the technical aspects of the digital tools but also with their potential for promoting the development of one’s artistic and personal expression.

I recognize this observation. If we merely use the digital tools to make our work in the studio more efficient, we miss out on the potential for professional development they also hold.

Flemming Tvede Hansen concludes the conversation in Kunstuff by underscoring the need to ensure that professional innovation is supported by practice-based research. A development that became a reality for the ceramics programme when The Danish Design School moved to new premises at Holmen in 2011.

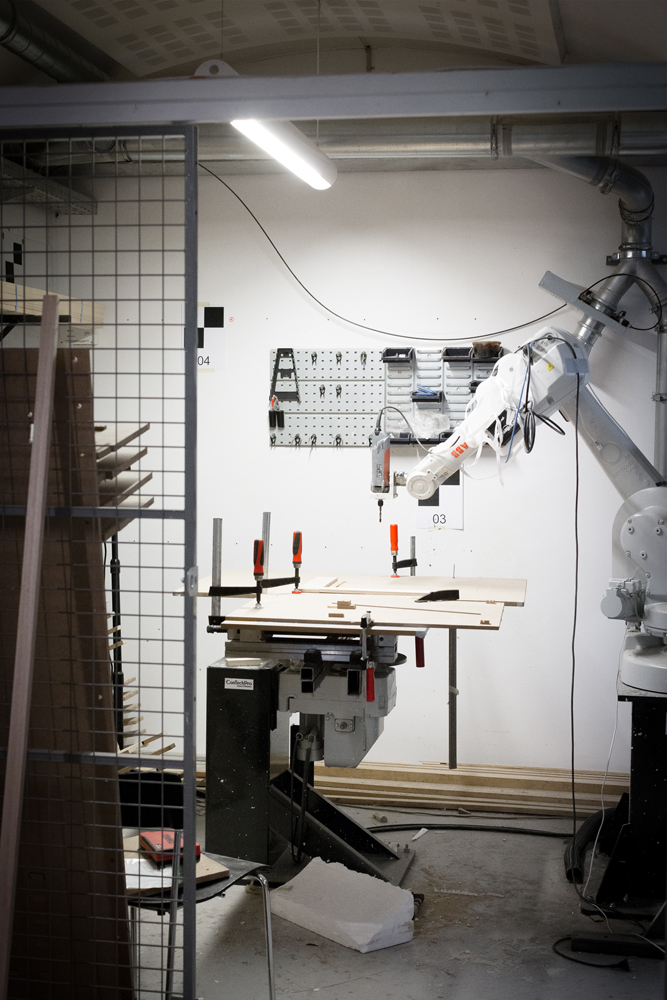

The move made it possible to rethink the workshop as well as developing a teaching approach where the experimental approach to materials goes hand in hand with both traditional ceramic methods and digital technology. The ideas from 2011 are still alive, for example in the current courses, where first-year students collaborate on experimental processes in the workshop.

There are many different views about the workshop courses in the education programmes. Critics question whether the schools may be losing high-level craftsmanship as the emphasis moves more to design and interdisciplinary approaches and away from craftsmanship and specific disciplines. I see the digital tools as possibilities for developing craft and giving it a voice in a time of profound change.

As I see it, craft makers need to adopt an experimental approach to and with their craft practice. At the same time, I welcome the critical voices from the field, as they help to inform and enhance the development taking place in the educational programmes.

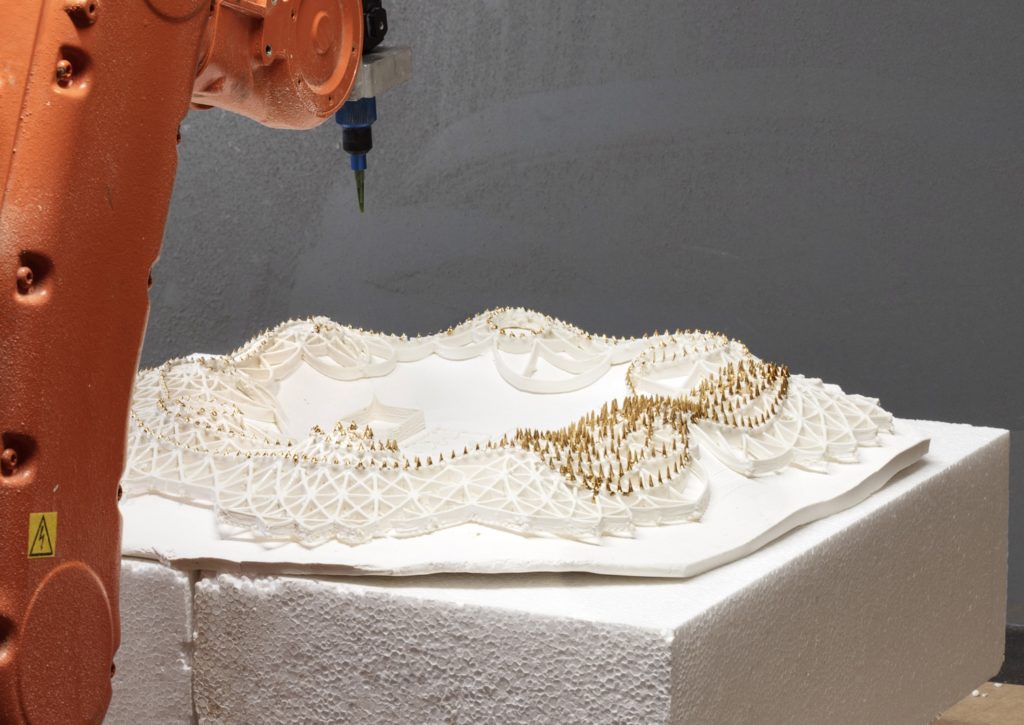

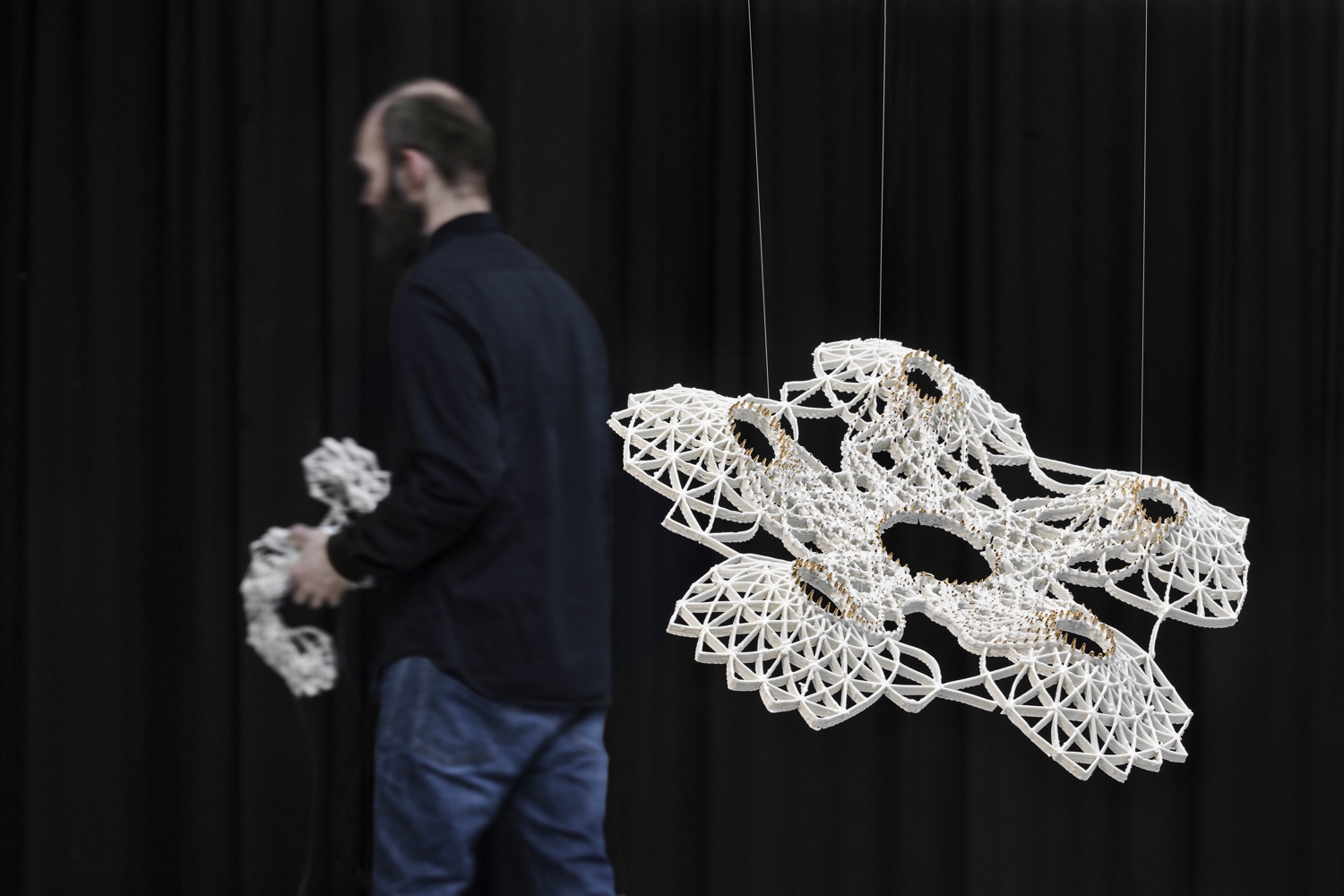

While Flemming Tvede Hansen in his PhD project had to transfer the digitally printed plastic object to the ceramic material, his piece “Filigree Robotics”, which was shown at the Danish Biennale for Craft & Design in 2017, illustrates the development of 3D printers in general and their specific use in the field of ceramics.

In “Filigree Robotics”, porcelain clay is printed directly onto a curved mould according to a generative algorithm, resulting in a series of lace-like ceramic objects. The piece was subsequently glazed and fired. It is one thing to print with porcelain clay directly, but the 3D base and the generatively developed print pattern also explores the capability of the digital tools and our notion of what a ceramic object can be.

“Filigree Robotics” is a ceramic object of art, but it is also a practice-based research project and the result of a collaboration between two departments at the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen – Ceramic Design and the Centre for Information Technology and Architecture (CITA). Thus, it also illustrates how practice-based research and interdisciplinary collaboration can promote the use and development of digital technology in classic craft disciplines, in this case ceramics.

From treadles to mouse clicks

The digital development of looms has a longer history than 3D printing with clay. In 1802, Joseph Marie Jacquard patented a control system for looms based on punched cards, and in 1808, the jacquard loom was a reality. In 1968, IBM presented the first jacquard loom linked directly to a computer at HemisFair in Texas, in the 1980s, industry got access to electronic jacquard looms, and finally, in 1995, the hand-weavers joined the party, when Digital Weaving Norway sent the Single Thread Control loom, TC1, on the market. In 1998, the first TC1 landed in Denmark.

Danish Craft makers and weavers Grethe Sørensen and Lise Frølund secured the funding, and the loom was placed at Design School Kolding. The two makers are both included in the exhibition World Wide Weaving, which focuses on works produced on this type of loom and which is shown in Kolding in spring 2022. The loom could be used by both students and professionals, and it was easy to work with, as it could read bmp-, jpg- and tiff-files, provided they only consisted of black and white pixels.

In parallel with this development, electronic shaft control became more common in the educational programmes and digital looms and weaving programs have played a significant role for the way weaving is taught today.

A growing number of weavers took on the challenge of exploring the possibilities provided by the Single Thread Controlled loom. Kirsten Nissen’s project “Håndens arbejde” (Manual Work), which was presented at the Danish Biennale for Craft & Design in 2004, is a good example of how a digital tool can inspire new approaches to pattern generation. In an interview in Kunstuff, Kirsten Nissen says:

‘The history of textiles shows that new technologies generate new products and new forms of expression. So I want to explore whether the computer can take me in new directions and create patterns that my imagination can’t manage.’

In the interview she also explains that she has created a pattern generator that creates the weaving design based on physiological measurements made during the weaving process. The piece was woven on the TC1 loom at Design School Kolding.

Boundless possibilities

In 2015, a group of students from textile, fashion and communication design at Design School Kolding worked on the joint bachelor project Abstract_. Their focus in the project was on involving the end user in the design process. To that end, they invited potential users to write a personal text on the computer while a web camera program read their facial expressions. This input generated patterns based on parameters the students had defined in the program.

This process let them design textiles for clothing where the weave or knitting pattern or the textile print was based on the end user’s choices. In this project, the three students used and explored the digital tools available to them at the time in exemplary fashion. As in the example of “Filigree Robotics”, both profound disciplinary mastery and interdisciplinary collaboration were key in exploring the full potential of the digital tools.

Digital tools, manual work and finely tuned sensory sensibility

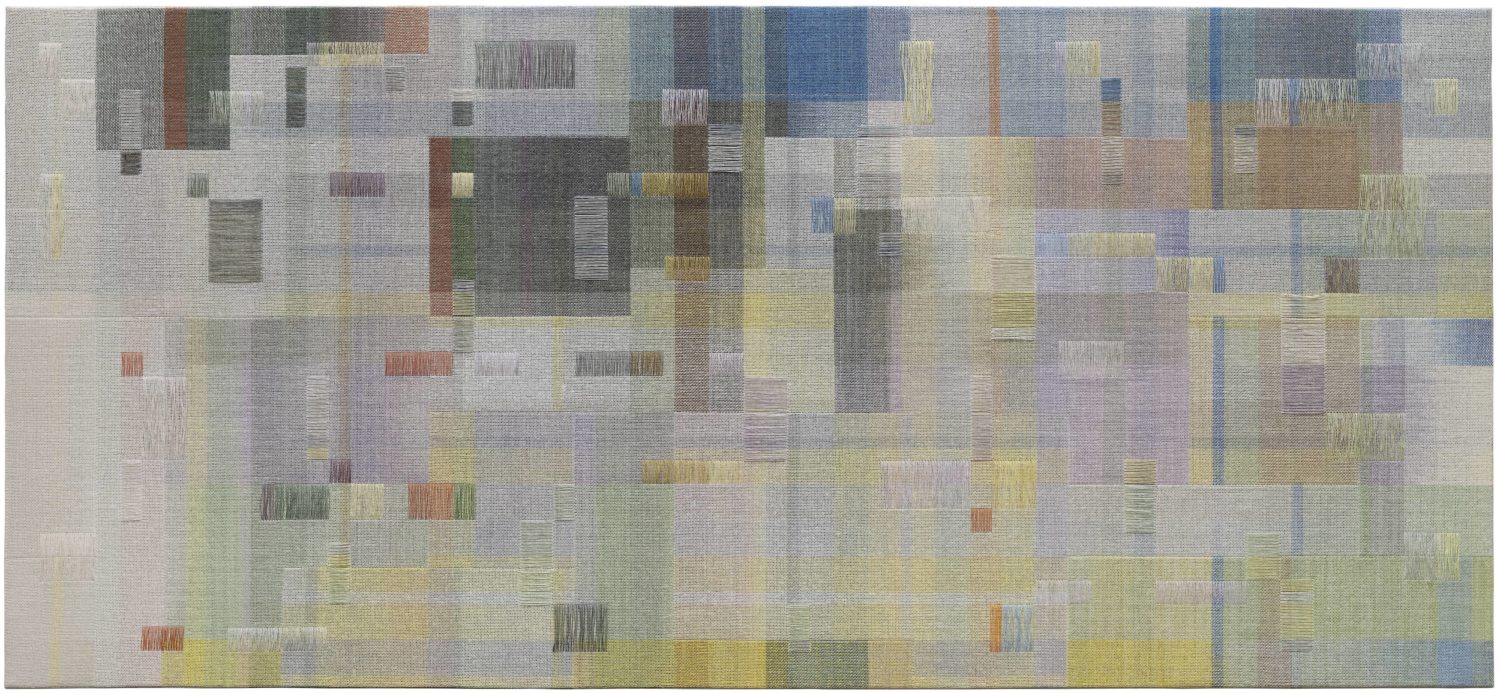

The latest example – and the last in this context – of a craft maker combining digital tools with manual work is Anne Mette Larsen’s exhibition project “Toskaft fra højbedet” (Two-Shaft From the Raised Flower Bed) from 2021. Anne Mette Larsen has a consistent interest in squares, colours and multi-layered plain weave. These are elements that can be explored on a traditional foot-powered loom, so how does she benefit from using the digitally controlled looms she has been exploring and working with since the 2000s?

Anne Mette Larsen combines the digital tools with her professional knowledge about weaving in sections and layers, blending colours by combining threads, adding extra intersections and applying a finely tuned sensory sensibility to the expression she is aiming for. The result is pieces that are highly complex to read, notwithstanding the simplicity of their underlying logic. The project illustrates how profound mastery of techniques and materials can be further refined by incorporating the digital tools that are available.

What the future holds

By January 2022, the computer has long since become a household item, and for professional craft makers, knowledge about digital image processing and communication are taken for granted. The computer is also used as a design tool in a wide variety of ways, both through the application of sophisticated design programs and in combination with peripheral digital tools. However, digital tools such as a 3D printer for clay or a Single Thread Control loom are not household items.

In extension of the examples I have mentioned in this essay, it is worth pointing out, however, that the Danish Art Workshops have several different looms with electronic shaft control and a Single Thread Control loom, and that Guldagergaard – International Ceramic Research Center has a 3D printer for clay. Fab labs and maker spaces that offer access to 3D printers, laser cutters, CNC cutters and other digital tools are emerging in all the major cities. This means it is possible for practising craft makers to experiment and produce on the tools they encountered during their training.

The examples in the essay all suggest that professionalism and knowledge about materials play a crucial role for what can be achieved by means of digital tools. But what might be next? There is no doubt that the future holds many new exciting developments.

For example, 3D printed textiles that might enable a more sustainable and responsible use of materials? Virtual technologies are also making huge strides within craft and design. One local example is the VIA Design fashion shows.

In spring 2020, the audience could access the collections in a virtual reality universe, and in spring 2021 the show was presented in people’s homes via the app Sustain:ar. Virtual technology was also highlighted in the seminar that was held in connection with the Biennale for Craft & Design in 2021, and in the international arena we have seen the first digital dress fetch a very high price indeed.

It has to be only a question of time before we find it natural to buy and style our virtual universes with exquisite craft objects! Wonder what the material and knowledge about production and the processing of materials will mean when we reach that point?

Anne Louise Bang, Senior Associate Professor, PhD

Anne Louise Bang is a textile designer and a researcher specializing in sustainability and design at VIA University College’s Research and Development Centre for Creative Industries and Professions. Bang’s research is practice-based and experimental and carried out as Research Through Design. Her main interests are sustainability, textile and interpersonal dialogues based on physical materials and sensory sensibility.

References

Albers, A. (2017). On Weaving: New Expanded Version (s. 44). Princeton University Press.

Gelfer-Jørgensen, M. (2014, 6. juli). Kunsthåndværk (Craft). I Den Store Danske.

Hansen, F. (2010). Materialedreven 3d digital formgivning: Eksperimenterende brug og integration af det digitale medie i det keramiske fagområde. Danmarks Designskoles Forlag.

Kaldahl, M. (2009 vol 3). Computeren og leret. Kunstuff , s. 20-24.

Kig med indenfor på SuperFormLab – Designskolens nye laboratorium for keramikdesign og 3D-formgivning. Det Kongelige Akademi. (2012, 15. marts)

Wallach, M. (2021, 27. september). Flemming Tvede Hansen og Maria Sparre-Petersen. Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet.

Liquid Life. Biennalen for Kunsthåndværk & Design 2017. Katalog udgivet af Danske Kunsthåndværkere & Designere.

Hansen, F. T. Projects.

Møller, M. (2020, 7. maj). Joseph Marie Jacquard. I Den Store Danske.

Bang, A., Trolle, H., & Larsen, A. (2016). Textile illusions: Patterns of light and the woven white screen. I N. Nimkulrat, F. Kane & K. Walton, (red.). Crafting textiles in the digital age (s. 48). Bloomsbury.

Works woven on TC1&TC2 on display in Denmark! Digital Weaving Norway.

Bang, A., Trolle, H., & Larsen, A. (2016). Textile illusions: Patterns of light and the woven white screen . I N. Nimkulrat, F. Kane & K. Walton(red.). Crafting textiles in the digital age (s. 50-51). Bloomsbury.

Mangfoldighed. (Biennalekatalog). Biennalen for Kunsthåndværk & Design 2004.

Schultz, M. (2004 vol 3). Håndens arbejde i en teknologisk tid. Kunstuff , 12-15.

Larsen, A. M. (2021). Toskaft fra højbedet

Larsen, K. R. Hvad vi tager med fra TAKEAWAY? Biennalen for Kunsthåndværk & Design 2021

Iridescence. The Fabricant.

Search the Arkivet

In the archive you can search in journals from 1948 to 2009 as well as in the new publications on Formkraft. For example: