Jewellery is something we carry close to our bodies, and as such, it becomes a part of our personality. We keep jewellery in jewellery boxes at home because they are precious to us. We fear losing them, perhaps because we inherited them from a dear relative, or they are connected to a special event. But what happens to the jewellery when Copenhagen transforms into the City of Jewellery, when the jewellery moves from the private sphere to the public space? When we wear jewellery and talk about jewellery, they tell us stories that connect personal history with collective history.

Architectural Connections

City of Jewellery spanned over three days with more than 30 different exhibitions from September 28th to 30th, 2023, organized by the Goldsmiths’ Guild of Copenhagen. With the theme “Connections,” visitors could witness firsthand, at open workshops, stores, and galleries, how goldsmiths and silversmiths create personal, handmade jewellery closely connected to the body, clothing, space, and design history.

My journey began at the exhibition “Architectural Connections.” The idea behind the exhibition was to create a meeting between jewellery artists and designers with a professional background in architecture. This year, City of Jewellery coincided with Architecture Capital ’23 and Architecture Day. Jewellery artists with an architectural background emphasized this connection by making Copenhagen the site-specific focal point in their works for the exhibition.

One of the exhibitors, Michala Eken, shared that as both an architect and a jewellery artist, she works on multiple scales and sees elements of jewellery everywhere, just as she also finds urban elements in her jewellery.

“Is it a ring – or is it a pavilion? Is it a weather vane, or is it a pendant? An earring or a lamppost?”

She refers to her new series of works created for City of Jewellery as ‘City Jewels’ because they tell a story about those who wear them. Jewellery endures and is passed down from one generation to the next, continuing to carry meaning.

Michala Eken particularly explores the connection between tradition and renewal, as the foundation of her design practice acknowledges standing on the shoulders of tradition. She does not seek to invent something entirely new but expresses herself with and collects existing typological vocabularies. She incorporates memory into her jewellery.

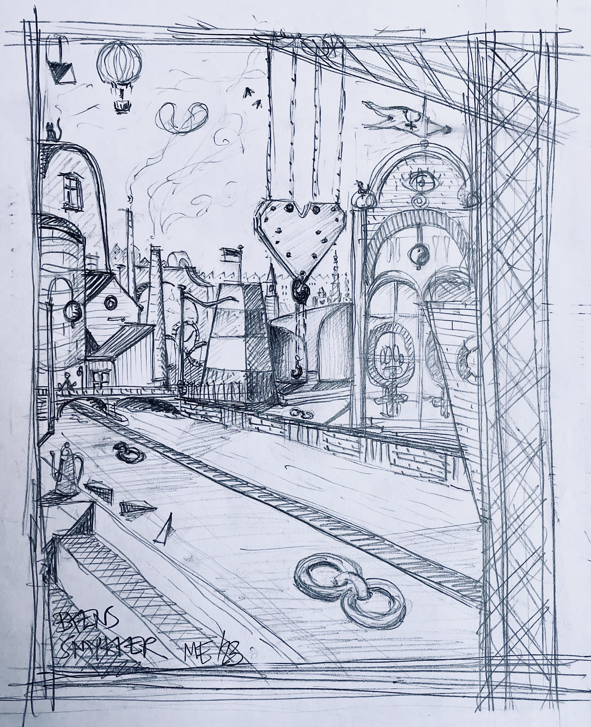

Users can recognize this memory, as it lies as something fundamental or inherited in all of us – a collective memory – from which we can all draw inspiration, to varying degrees of awareness. The imaginative and poetic visual language she creates with coffee pots, weather vanes, cranes, and chimneys in a surreal universe is inspired by the Italian architect and designer Aldo Rossi (1931-1997).

In the sketch below, you can see Michala Eken’s distinctive signature both in the weathervane at Dannerhus

With the jewellery series ‘City Jewels,’ Michala Eken has employed a highly specific, site-specific choice of motifs that speaks to a collective memory of love for the city’s details and the joy derived from the objects encountered in our shared surroundings. When these motifs take the form of jewellery worn on the body, new ways of experiencing these objects emerge, and new narratives unfold. This can open up conversations and exchanges of shared experiences between those wearing the jewellery and those they encounter along their way.

According to Eken, her jewellery, through their almost provocatively simple design, engages in cultural criticism. The jewellery can serve as carriers of more or less direct references to topics relevant to society. They are always welcome to become conversation pieces that foster dialogue and connection. Her works are generally simple, bordering on the understated.

Souvenirs and discarded items elevated to jewellery

Another exhibitor, Caroline Wegener, conducts an exploration of three different urban spaces with her Copenhagen Jewellery. She poses questions such as: What does this space mean for those who live in the city? What impression does the space leave on you when you are in it or just quickly passing by? This inquiry has resulted in three distinct jewellery series.

Rings called “Voices” take inspiration from the classic signet ring design and draw upon the colors, lights, advertisements, and capital of Rådhuspladsen. These rings convey a sense of masculinity and power, with fragments of logos leaving their mark on the wearer, perhaps without immediate recognition.

The interpretation of The Black Square on Nørrebro comes to life in a vibrant and eclectic chain known as “Souvenirs.” The term “Souvenirs” suggests that a memory is embedded in an object, capturing recollections of journeys, places, or events. Originally, souvenirs were travel trophies symbolizing triumph over challenges, signifying a journey of personal growth. In Caroline Wegener’s creation, Souvenirs becomes a piece of jewelry without a fixed form, reflecting the dynamic life in the neighborhood amidst changing residents and a fluid cultural identity.

A different series, “Tickets,” consists of five brooches inspired by admission tickets to the Statens Museum for Kunst. These brooches transform the value of entrance tickets into a form of wearable art. Once the cultural visit concludes, the admission ticket, typically discarded, gains renewed value when worn as a gemstone in a brooch, evolving from urban waste to a cherished piece of jewelry.

Caroline Wegener’s work involves collecting and elevating discarded items from urban spaces, influenced by the ideas of philosopher Walter Benjamin. Benjamin, known for his writings on the significance of collecting, describes the collector as someone with a unique perspective, often noticing things that society overlooks—old shoes, discarded teddy bears, peculiar buttons, or feathers. The act of collecting serves as a reminder to explore the peculiar and marvelous aspects of our surroundings, often forgotten in our fast-paced reality.

Connections Between Generations

In another exhibition, “Connecting the Dots,” in the City of Jewellery, the overarching theme of connections is explored by pairing three well-established jewellery artists with three recent graduates. The older generation aims to establish a connection with the younger generation, providing them with an opportunity to establish themselves in the jewellery art scene and understand the dynamics between the old and new generations, investigating the direction jewellery art is heading.

Lin Rosenbeck belongs to the younger generation and, like the other mentioned jewellery artists, has a keen eye for everyday life in her collection of pasta jewellery. She describes her practice, expressing that her joy in jewellery art stems from an interest in small, peculiar, and abandoned objects. In her practice, she works with everyday items found at home, on the street, and in nature. She is fascinated by the potential and stories these objects carry—what purposes they have served, how they ended up where they did, and what happens when you pick them up again and introduce them into new contexts with the body. She perceives her practice as a form of caregiving, where even the most commonplace or seemingly unremarkable little thing is given space and meaning, highlighting that it is worth cherishing and preserving.

The series “Everything My Child Eats” revolves around the life-changing experience Lin Rosenbeck underwent when becoming a mother to her first child in 2022. In this collection, everyday materials such as jewellery and raisin boxes come into play. The jewellery sheets are shaped like raisin boxes with threads cut using the jewellery mill wheel’s holes. The artworks refer to both her role as a mother and her work as a precision mechanic.

The elemental quality and the fragility and delicacy that jewellery adds to the jewellery prompt us to see everyday materials with new eyes. In philosopher Walter Benjamin’s writings on Paris, the collector is portrayed as an outcast figure finding justification for existence through the city’s refuse, cataloguing the forgotten through their collecting activities.

Lin Rosenbeck resembles Benjamin’s collector by having a special eye and sensitivity to things, rescuing the forgotten and repressed in her jewellery. This draws a parallel to Benjamin’s idea that there is potential for salvation in what is forgotten and repressed, and the collector can be seen as an embodiment of this potential.

The collector can be viewed as a modern storyteller, a similarity that extends to the designer sharing stories recognizable to the user. These stories aim to provide a greater understanding of our spiritual and material conditions. There is also a connection between Walter Benjamin’s characterization of the collector and the concept behind the City of Jewellery.

Benjamin mentions the ragpicker, who emerges in cities as larger quantities of waste are produced. According to Benjamin, the ragpicker is a symbol of human poverty, an individual cast out by society, subsisting by collecting what the city has discarded. The ragpicker catalogues the forgotten through their collection. In Pariserpassager, Benjamin argues that the crucial aspect of collecting is freeing objects from their original functions, detached from their utilitarian purposes.

For the collector, each small thing becomes a form of knowledge about an era, about the landscape, about industry. When Lin Rosenbeck combines classical craftsmanship with a modern approach to unconventional materials, the works encompass both humour and tenderness.

Marie-Louise Kristensen represents the established generation of jewellery artists and, like Lin Rosenbeck, is immersed in personal stories and poetic associations. With a keen sense of observation and the ability to expand upon them creatively, she creates works that process our close, Danish everyday life as a sensory, memory-laden experience.

For instance, the jewellery series BAYERISCHE TRÄUME (Bavarian Dreams) is inspired by her stay at the Akademie die Bildende Künste in Munich. During her journey, she discovers the challenges of navigating the city as a tourist, finding it foreign with a different language, lederhosen, and distinct jewellery like traditional Bavarian men’s jewellery. Marie-Louise Kristensen incorporates the Bavarian light blue color in her Daisy flower, referencing Queen Margrethe’s nickname Daisy, which inspired the ‘Daisy’ flower brooch designed by goldsmith A. Michelsen. Moreover, during Marie-Louise’s stay, Queen Margrethe II was on a state visit to Munich.

There is a fragility and a childlike, playful fantasy at play when she adds dental mirrors to her little jewellery cave. This involves a cultural critique, as the mirrors present perspectives on the world that the wearer of the jewellery wouldn’t normally see.

Memory Jewellery

In another exhibition, “101 Charms – a Tradition Reinterpreted,” charms are perceived as small stories that can be milestones in people’s lives. Charms are talismans that protect us. They can be small souvenirs from an event but can also be a gift from your beloved, expressing their love, which you cherish.

We all carry our stories with us, and constantly, we seek ways to remember or commemorate an important event in life. Seashells might be the first jewellery objects worn as charms. The ancient Egyptians used charms as talismans. The first known woman who worked with charms was Queen Victoria, who created small charms when her husband died. Her charms, seen as a remembrance for the bereaved, became a fashion craze in the 1700s.

A souvenir is not merely a memory of a place or a person but can also be a remembrance of human mortality (memento mori). Jewellery artist Mette Saabye shares that when her father passed away, she inherited the family casket containing small art objects that her ancestors had placed in the drawers for future generations to remember their family history, identity, and individual family members. In one of the small drawers, there are hair ornaments that a sister made for her brother when he went off to war. They were intended as encouragement, comfort, and protection.

She, in turn, has collected locks of hair from family members who play or have played important roles in her life. Some of these locks are incorporated into her charms in this exhibition. The piece ‘Lykkeknude’ (Happiness Knot) is formed from her and her daughter Felicia’s hair. The name Felicia is derived from Latin Felix, meaning happy or one who brings happiness. A love charm, the tricolored braid symbolizing unconditional love, is made from her and her daughters’ hair. The amulet for protection against all evils, sickness, and death is a secure little nest made from her grandmother’s hair.

The act of designing thus involves a consideration of temporality, encompassing the past, present, and future. Charms, at certain times, become popular, such as in the 1970s with the so-called tooth jewelry. Charms create a connection to the past, in the form of gifts we have received and souvenirs we have purchased during a journey, like the leaning tower of Pisa or the Little Mermaid. The exhibition is structured with one long bracelet, approximately 9 meters in length, where the 101 charms are suspended. The bracelet circulates throughout the exhibition.

Kim Buck engages in cultural critique in his charm “Lise – en gammel flamme” (Lise – an old flame), which addresses the disappearance of small local stores like Irma. In the end, Lise is only found as a memory in the form of a simple silver charm. Here, Kim Buck shares a resemblance with the collector as he passes on stories recognizable to a user. These stories aim to provide a greater understanding of our spiritual and material conditions. Once again, it revolves around the idea that memory in design requires time and reflection, considering it as a process and a form of wonder that breaks with our habitual thinking, as exemplified by Kim Buck in his design. This means that not all users will understand and appreciate his design. The designer has a special eye for things that he wants us to take notice of, as he juxtaposes the present and the past through his own interpretation of the world.

The collector, as a figure, plays a significant role among the jewellery artists in the City of Jewellery. A collector can be viewed as a modern storyteller, possessing a special eye and sensitivity to things, reflecting a profound democratic perspective on the material world because nothing inherently surpasses something else. The inexpensive can be more valuable than the expensive. Designers resemble collectors when they share stories recognizable to users. These stories aim to provide a greater understanding of our spiritual and material conditions. Danish jewellery designers are perceived as activist and progressive in this context. They show us that something is at stake in our time. They prompt us to marvel at our world with their unique perspective on things they want us to notice. Through their jewellery, they open doors to dialogues and connections.

Facts

Kjøbenhavns Guldsmedelaug organizes ‘Smykkernes By’ (City of Jewellery) in Copenhagen. A digital program guides visitors to exhibitions and events where they can experience the jewellery. In 2023, the theme was Connections (Forbindelser).

Sources

Adjmi, Morris, and Giovanni Bertolotto. *Aldo Rossi. Drawings and Paintings.* Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.

Benjamin, Walter. “Der Sammler” in *Das Passagen-Werk*, Erster Band. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1982.

Benjamin, Walter. *Fortælleren og andre essays*, overs. Kbh.: Samleren, 1996.

Exhibitions

101 Charms – en tradition nyfortolket

Receive a newsletter

Sign up for Formkraft’s newsletter and receive information about new articles as well as tips on relevant conferences and books. Sign up here.