We live a life entangled and closely connected with materials. Take a look at all the functional objects in a one-metre radius around you and try to analyse their material composition. That will make you lose your breath, right? We are deeply dependent on all sorts of materials, and we squander them with a sense of greed that turns to indifference as soon as the product’s novelty value wears off.

On 30 March 2022, the European Commission passed a new law developed in collaboration with the Council on the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation. The goal of the new law is to make sustainable production the new norm in the EU, with an emphasis on circular eco-textile systems, durability, increased lifecycles, repairability, reusaubility and the use of recycled fibres.

With materials piling up all around us, it might seem absurd to even talk about sustainable manufacturing. However, by addressing topics such as durability, longer lifecycles and repairability, the EU is promoting a cultural transformation that is worth fighting for.

This shift will require fundamental changes in values and norms, which will no doubt be a tough and arduous process. It will also require an ethical compass and heightened awareness of the fact that the materials around us are processed nature and often continue to exist long after they are out of our hands.

So how can we change the way we relate to the materials around us and allow greater awareness of the life of materials to sow a seed and take root in us?

With her book Vibrant Matter: A political ecology of things (2010), the American political philosopher Jane Bennett (b. 1957) seeks to open modern consumers’ eyes to the life of materials. Bennett’s theory will be briefly introduced in this text, because she calls for a break with the notion of articles for everyday use as dead and inanimate. Our general tendency to separate life and matter causes us to ignore, for example, the tendency of waste to develop into lively chemical flows.

Bennett uses the term ‘vitality’ to refer to the ability of things to disturb or hamper human plans, as it happens time and again when pollution emerges at micro- and macro-levels in nature all over the globe. We are incapable of controlling how manmade materials develop in confrontations between people, nature and other materials.

When material compositions meet, they may develop specific inclinations that defy our control in these fleeting encounters. That is the case, for example, when textile made of plastic leaves chemical traces on your skin or when plastic bottles or cigarette butts are tossed in nature, and their exposure to rainwater, soil, fungi and plants initiates toxic chemical processes.

The notion of lifeless articles of daily use leads to earth-destroying consumption

‘Why advocate the vitality of matter? Because my hunch is that the image of dead or thoroughly instrumentalized matter feeds human hubris and our earth-destroying fantasies of conquest and consumption.’ (Bennett, 2010).

With this statement, Bennett introduces her book and advocates a philosophical and political understanding of materialities. Her political project has the ambitious goal of driving new legislation and bureaucratic programmes aimed at securing a sustainable focus on lively things through enhanced sensibility. Bennett writes, ‘How, for example, would patterns of consumption change if we faced not litter, rubbish, trash, or “the recycling,” but an accumulating pile of lively and potentially dangerous matter?’.

The new EU legislation enhances the focus on the durability, reusability and repairability of materials. However, from the perspective of Bennett’s philosophical project, this is not enough. Enhancing sensibility more broadly calls for an ontological perspective that explores the agency of nonhuman things. This is where Bennett moves beyond the conventional perception and understanding of materials. Although she does not go as far as Bruno Latour (1947–2022), who proposed convening a ‘parliament of things’, she insists that we too consist of nonhuman materialities.

The food you eat is nonhuman matter with the potential to alter your mood or your weight, for example. Or take lotions and hair products containing glitter that consists of chemicals with the potential to cause health problems over time. The growing consumption of palm oil in everything from dishwashing liquid to sweets is leading to clear-cutting of fertile land and the destruction of important ecosystems.

Bennett writes,‘In a world of vibrant matter, it is thus not enough to say that we are “embodied.” We are, rather, an array of bodies, many different kinds of them in a nested set of microbiomes. If more people marked this fact more of the time, if we were more attentive to the indispensable foreignness that we are, would we continue to produce and consume in the same violently reckless ways?’ (Bennett, 2010)

Vibrant waste possesses both power and agency

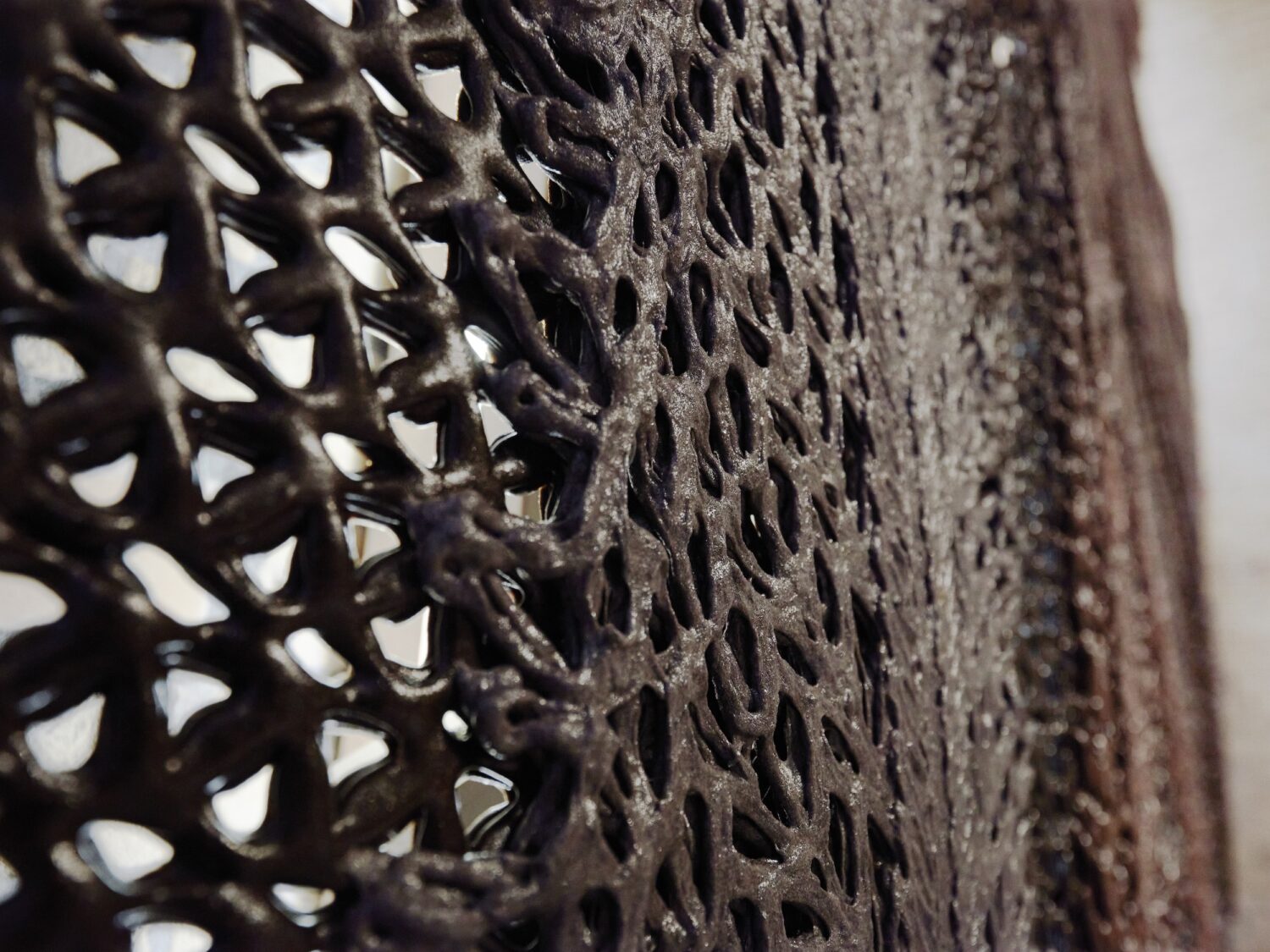

Recently, the Royal Danish Academy presented the exhibition Planetary Boundaries – Rethinking Architecture and Design, which exemplifies how the limitations of the planet and the vulnerability of the ecosystem require us to rethink materials, design and architecture. One example of consideration for material properties and behaviours over time in the choice of building materials and in the preservation of the existing building stock is the use of biogenic building materials.

These materials are regarded as living from the early stages of the design process; an approach that is well aligned with Bennett’s view of materials as living nonhuman bodies collaborating in assemblies of functional objects. However, Bennett takes this understanding one step further, viewing humans and nature in a fluid interface; a variant of materialism known as New Materialism.

Bennett’s main topic is functional objects, such as waste and metal, but she also discusses food as a category. This broad scope makes her thinking relevant to designers, craftspeople and consumers, among others. To explain what happens in the interaction of human and nonhuman forces, she uses the terms actor, agency and assemblage.

Drawing on Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, Bennett adds the concept of agency: the actor’s potential for action. The agency of waste, for example, depends on the potential and agency of other organisms. In creative terms, an assemblage may thus be described as a colourful collage, in which the interactions of humans and vibrant matter unfold, function or vibrate in multiple dimensions: ‘Humanity and nonhumanity have always performed an intricate dance with each other’ (Bennett, 2010).

Bennett’s discussion incorporates philosophies of nature, which have roots going back as far as antiquity. While the philosophical discipline of epistemology deals with human perception of the world, ontology explores the actual nature of reality or the world.

Today, drawing on the science of physics, we might call these building blocks atoms, particles and energy, but Bennett proposes an ontological approach to matter, viewing matter as living, vibrant and engaged in a kind of symbiosis of actants that combine to influence us in potentially very powerful ways.

We need to move beyond our self-centred worldview and try to understand the mutual interactions of materials. In her book Hvordan skaber vi bæredygtig udvikling for alle? [How do we create sustainable development for all?], Professor Katherine Richardson, leader of the Sustainability Science Centre at the University of Copenhagen, defines systems thinking as a way to ‘understand and act on interactions’ (p. 28).

According to Richardson, modern Western society has lost its capacity for systems thinking because the natural sciences – in part as a result of Newton’s breakthroughs in physics in the 17th and 18th centuries – went from taking a holistic view to studying nature as individual components embedded in a system. Richardson is an advocate of systems thinking as the way to minimize resource consumption for the planet’s 8 billion people in the near future, because it restores our regard for the significance of interactions. Similarly, Bennett could be seen as seeking to bring attention to interactions at a micropolitical level in an effort to promote greener versions of human culture.

The craftsperson’s dialogue with the material is also a dialogue with nature – which should be incorporated into our education system

In-depth knowledge of a material and the way it behaves in a design process takes many years to achieve. It develops in a dialogue with the material and, thus, a dialogue with nature through the material. In my opinion, craft-based experience and hard-earned knowledge about materials are seriously underrated in our current effort to develop sustainable solutions to address the severe pollution of our planet.

As basic craft skills are no longer commonplace, our knowledge of the materials around us and their qualities has diminished. I take the liberty of pointing to the role of education and crafts in developing this sensibility; topics that receive limited attention in Bennett’s work. Didactics and educational approaches can play a key role in the effort to build the sort of sensibility to materials that Bennett advocates.

This calls for an educational approach where lecturers and researchers make the students examine their own view of nature, including dogmas, norms, values and taken-for-granted assumptions. We do not all have the same view of nature, and our different views influence our understanding of the ways in which materials interact with nature. The authors of the book Sustainability in Creative Industries: Perspectives from the field of education in design and business provides interesting insight into how creative education programmes approach sustainability and the challenges they face. How do we educate people for an unknown future?

It is interesting to see how a design approach based on Bennett’s view of materials as living nonhuman bodies might contribute to the design and production of, for example, textile materials that are less harmful to nature and people. This is already happening in various research contexts. For example, Klothing at the Royal Danish Academy and VIA University College’s Centre for Sustainable Textile Production experiment with and study new approaches to textile.

However, for the new EU legislation to influence manufacturing norms, children and young people – the workers and consumers of tomorrow – need to develop a deeper understanding of sustainability. That is the goal of the Danish partnerships for Uddannelse for Bæredygtig Udvikling (UBU) [Education for Sustainable Development], and fortunately, the terms ‘environment’ and ‘climate’ have now been added to the stated purpose of upper-secondary education.

The new focus requires upper-secondary students to relate to the world in a reflective and responsible manner with particular emphasis on environment and climate. My contribution to the book Fodspor i Evigheden: Bæredygtighed, pædagogik og dannelse [Footsteps in eternity: Sustainability, education and culture], an anthology of many diverse voices from the landscape of education on the topics of sustainability and educational approaches in upper secondary education reflects my hope that primary and lower secondary school will similarly embrace sustainability as a fundamental value.

Knowledge of sustainability in relation to materials will give young people insights that they can use as future architects, engineers, physicists and designers. Acquiring basic craft skills for their own personal use later in life will also enhance their appreciation of sustainability as future consumers. This will make it easier for them to recognize and avoid poorly made products and thus help to promote new norms in consumer habits in alignment with the EU’s ambitions of promoting new norms in manufacturing.

Aging gracefully: Patina as an objective of the design process

With Bennett’s theory in mind, I have often wondered what would happen if the aging of vibrant materials was included as a key factor in the design process. Knowing a craft lets you know what to consider in the design or development process to make sure your material ages gracefully. Perhaps you are drawn by fascination with the aesthetic beauty that comes with patina. Old buildings or furniture in particular will take on a unique glow with wear and use.

However, not everything ages gracefully. Requiring all materials to age well will require new norms. It will require a new approach to trends. It will also require continuous maintenance, and that in turn requires craft skills, which need to be reintroduced into our everyday life, primary and secondary education, youth education and design education.

Sources

Bennett, Jane: Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press Books. 2010.

Richardson, Katherine: Hvordan skaber vi bæredygtig udvikling for alle? [How do we create sustainable development for all?]. Informations Forlag. 2022.

Strarup, Mads (Ed.): Fodspor i evigheden: Bæredygtighed, pædagogik og dannelse [Footsteps in eternity: Sustainability, education and culture]. Systime. 2023.

Links to more knowledge

Commission welcomes provisional agreement for more sustainable, repairable and circular products

Planetary Boundaries – Rethinking Architecture and Design

Biopolymer 3D print og Radicant

Nye ph.d.-projekter: Fra klimavenlige byggematerialer til inklusion

Sustainability in Creative Industries

-Perspectives from the field of education in design and business

Klothing – Centre for Apparel, Textiles & Ecology Research

Further reading…

Masters of materials

Craft makers and designers have a unique advantage when it comes to decorative projects, installations and building-integrated art in the public space: an in-depth grasp and knowledge of materials.

Glass artist and Maria Sparre-Petersen, teaching associate professor at the Royal Danish Academy, sees new possibilities in an elastic field spanning from classic decorative projects to the virtual space that everyone now carries in their back pocket.

The durable, the quick and the tragically everlasting

How do we move away from the huge amounts of garbage and waste that are such a characteristic feature of our time? How do we rediscover the practice of caring for things that was a natural part of life for previous generations?

A conversation about aesthetics in practice

In a conversation with Vibeke Riisberg, Carsten Friberg, PhD of philosophy and an independent scholar of aesthetics, addresses her practical engagement with aesthetics in relation to sustainability.