Formkraft is a journal that engages critically with contemporary themes and aims to take part in shaping the future. The online platform, formkraft.dk, takes advantage of the new possibilities of the digital format and has to be in step with its own time in order to be relevant. However, in choosing a suitable name and creating a format that offers a viable path to the future, it is worthwhile to look at the antecedents and what we can learn from the past. The new journal has a long range of predecessors. Since the 1970s, the name has changed several times, and there have been suspensions of publication – something a new periodical would be loath to repeat. Still, the many predecessors form an impressive tradition. It is reasonable to trace the roots all the way back to Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri (Journal of Art Industry) from 1885. Launched by the Industriforeningen (Industrial Association), the journal was continued by Foreningen Dansk Kunsthaandværk Danish Society of Arts and Crafts), which was founded in 1901.

The new online successor not only has a digital publication format but will also be undertaking a digitization of the extensive back catalogue. As we look into the future, we aim to stand on the shoulders of this long tradition. Hence, we are going to link to older articles in the archive and introduce them as a current resource wherever it seems relevant. Even if our challenges lie ahead of us, we need to understand our strengths, ideals and tools by embracing our past experiences and history. We also need to understand our problems in light of the past, since the past was involved in shaping them. Others have faced similar situations and challenges before us. We can only hope that we are better situated to address them.

Timeline

Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri (Journal of Art Industry), 1885–99

Tidsskrift for Industri (Journal of Industry), 1900–71

Skønvirke, 1914/15–27

Nyt Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri (New Journal of Industrial Art), 1928–47

Dansk Kunsthåndværk (Danish Arts and Crafts), 1947–68

Dansk Brugskunst (Danish Applied Art), 1968–72

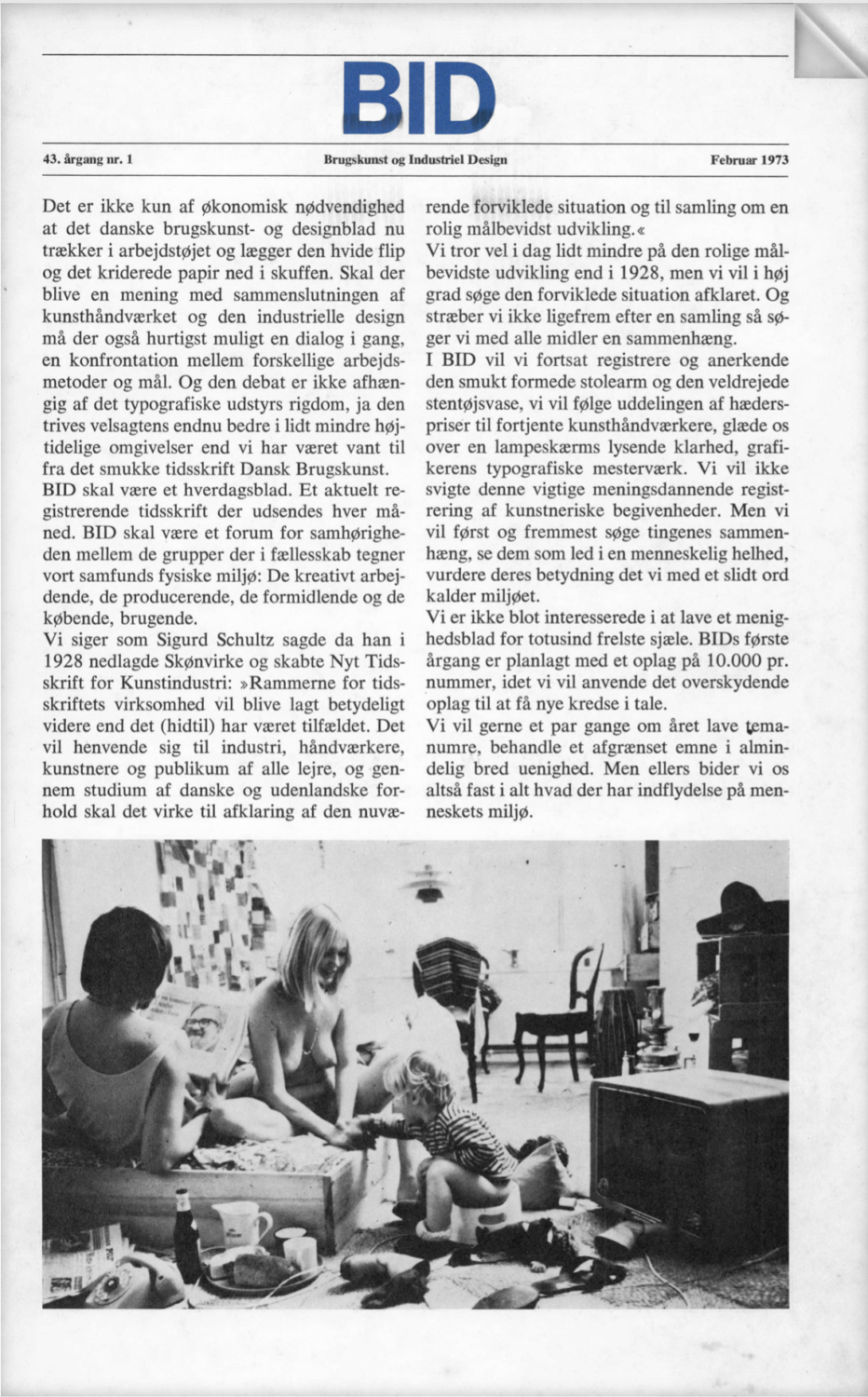

BID: Brugskunst og Industriel Design (Applied Art and Industrial Design), 1973

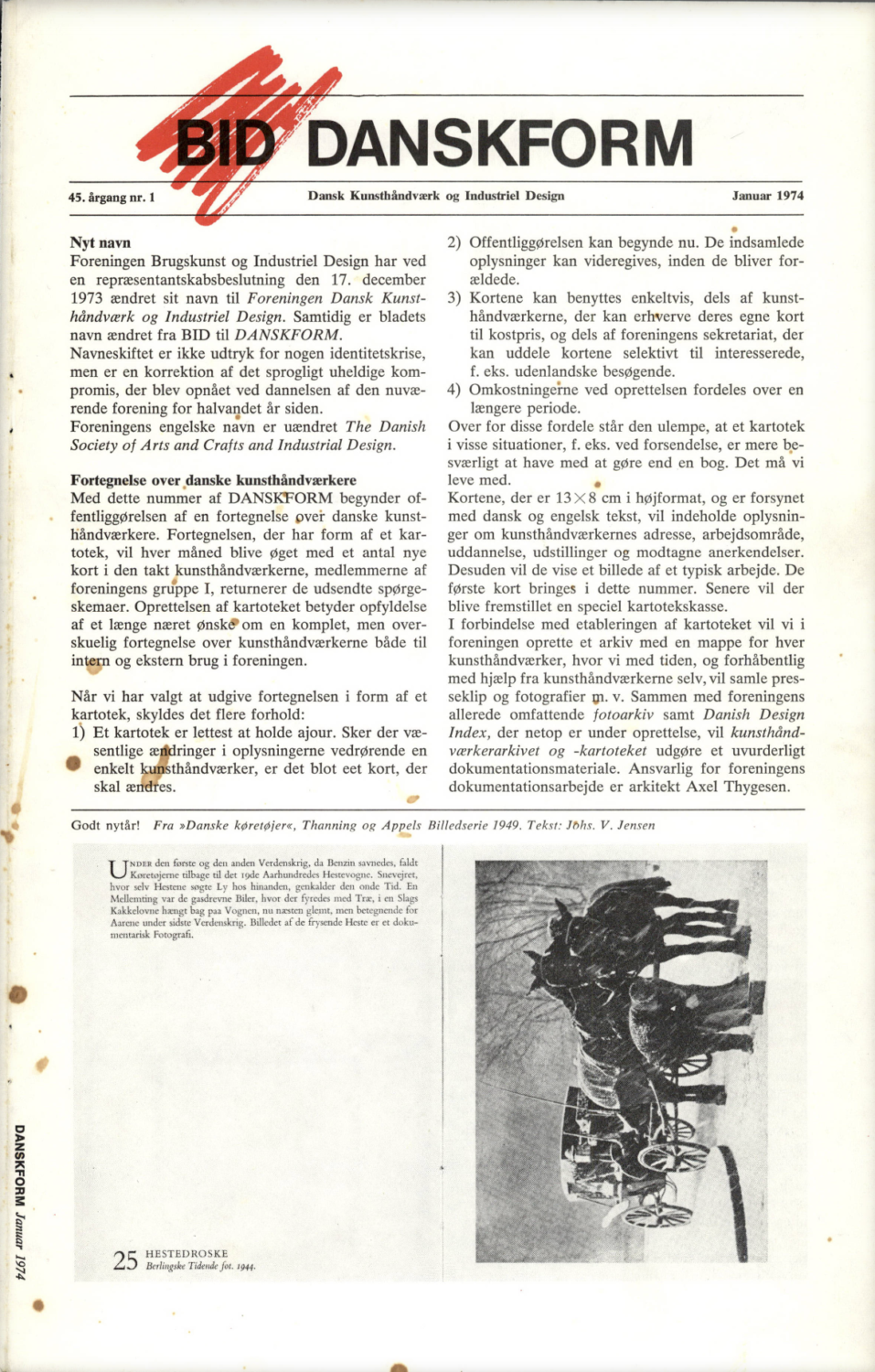

DANSKFORM (DANISHFORM), 1974

Dansk Kunsthåndværk og Industriel Design (Danish Crafts and Industrial Design), 1975

Danske Kunsthåndværkeres Landssammenslutning (National Danish Crafts Association), 1982–85

Dansk Kunsthåndværk (Danish Crafts), 1986–2004

Kunstuff, 2004-09+16

Times of crisis

Might we also learn from previous naming decisions? Well, we can see that naming has been a contentious topic, and that changes have typically reflected significant shifts in consumer culture as well as disputes about professional boundaries. One of the most dramatic changes occurred in 1973, with the introduction of the name BID: Brugskunst og Industriel Design Applied Art and Industrial Design). This change was occasioned by the 1972 merger of Landsforeningen Dansk Kunsthåndværk Danish Society of Arts and Crafts and Industrial Design) and Selskabet for Industriel Formgivning (literally Society of Industrial Form-Giving, its official English name was Danish Society of Industrial Design), but new editors also set a radically different course for the content, with articles that took a critical look at society and institutions. The layout underwent significant simplification, in part for the same financial reasons that had also motivated the merger and in part to create some distance from the artistic side and the refined presentation. There were strong statements about finally shedding the ‘arts’ term that was still present, both in the term ‘arts and crafts’ and in the more consensus-seeking term ‘applied art’. The new name also removed the national emphasis, where ‘Danish’ had long been part of the name of both the journal and the association. However, one of the very first issues of BID announced a competition to find a new name!

BID lasted just one year, as did its successor, DANSKFORM (DANISHFORM), which maintained the same format. These were the most critical years, resulting in a break between craftspeople and designers as well as a suspension of publication between 1975 and 1982. It was a difficult time, as both professions were changing and needed to define new roles for themselves in relation to the consumer society. Seen in a long-term perspective, the broad scope of topics becomes more striking, ranging from industrial products to craft objects and unique pieces. The challenge lay in finding new suitable terms that reflected the changing conditions.

In December 1973, BID presented the entries in the naming competition. The ingenuity was limited, and the proposals clearly aimed for a clear professional identity, whether in a return to the golden age, with ‘Dansk Kunsthåndværk’ (Danish Arts and Crafts), or, in a move in the opposite direction, Industriform (Industry Form). The prize, a Safari Chair by Kaare Klint, went by lot to Franka Rasmussen, a weaver and former teacher at the School of Arts and Crafts. When we set out to find a name for our new journal, we received many more – and excellent – ideas, even without putting up a prize. Although the suggestions were much more creative, that did not make the choice any easier. There are many criteria and issues to consider. To repeat the criteria from the competition in 1973: ‘1) The name should be short and idiomatic. 2) The name should lend itself to being translated into English if it cannot be used in its original version. (…). 3) The name should ideally cover the full scope of the association’s enterprise (crafts and industrial design).’ The current proposals typically contain no direct references to arts, crafts or design but seek to capture more fundamental and common interests in matter, texture and form. The rather abstract names may reflect that the professional identities are still under negotiation, exploring their positions in relation to the current time and tasks.

What’s in a name …

Looking back over the list of journal names, the short-lived as well as the more enduring, they reflect a field shaped by reform movements and professional positioning and repositioning. Terms such as art industry, arts and crafts, skønvirke, applied art and design represent different perspectives and ambitions but have often sought to cover an equally broad scope. Today, ‘art industry’ sounds dated. Between the 1870s and 1900, the trendsetters were the manufacturers of industrial art: porcelain manufacturers, silversmiths and the big cabinetmaker’s firms. They led the way in industry and the creative professions, establishing both craft training programmes and the Museum of Decorative Art (now Designmuseum Danmark), in addition to the journal! In a sense, they built the platform for Danish design culture. Mirjam Gelfer-Jørgensen portrays the diversity of the industrial art movement in her 2020 book The Joining of the Arts – Danish Art and Design 1880–1910. Initially, there was no contradiction between arts, crafts and design. When artists looked to crafts, they did so in search of inspiration and innovation, which in turn could also be translated into industrial products. As in the German Kunstgewerbe movement, Danish educational programmes placed a high emphasis on hands-on workshop activities to ensure that the students acquired a keen sense of both form and materials, also with a view to industrial manufacturing.

In a sense, Danish industry grew out of art industry around 1900. The name of the publication changed to Tidsskrift for Industri (Journal of Industry), although it continued to feature articles about both arts and crafts. Several new associations for crafts, handicrafts and decorative arts continued the artistic elevation of both popular tastes and ongoing experimentation through exhibitions, large-scale decorative and interior projects and, from 1915, the Skønvirke journal. As Gelfer-Jørgensen explains, the term skønvirke was coined by the head of the School of Arts and Crafts, Caspar Leuning Borch, in 1907. He complained (even then) that terms such as ‘applied art, art industry, decorative art, arts and crafts’ were not adequate. Although skønvirke later came to refer to a particular style, it was originally proposed as a term for the design practice of the time and applied to all types of tasks, from beer labels and artistic prototypes for mass production to interior design, decorative projects and unique pieces. This wide diversity was further broadened by an interest in exotic sources of inspiration, including Japan and other distant cultures, as well as national sources, such as traditional techniques. At the same time, there was also a celebration of the expression of ‘personality’, which highlighted the individual maker and project rather than a common style.

Proper industrial art or decorative art?

During early modernism, the older name was revived, now as Nyt Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri (New Journal of Art Industry), which proved long-lived, lasting from 1928 to 1947. It was published by Landsforeningen Dansk Kunsthaandværk and Kunstindustri Danish Society of Arts and Crafts and Industrial Design), a merger of existing associations. The debate was dominated by architects who were critical of the earlier focus on personality. In a newspaper op-ed in 1930, Poul Henningsen (known as PH) sneered at the notion of ‘atypical’ cutlery, which might cause one to ‘end up with Georg Jensen in your mouth instead of a spoonful of jelly’. Still, the architect-designers based their work on the education programmes and the many companies and studios that were a product of the past. (Paradoxically, it is these architects’ names and iconic designs we now associate with Danish design, not the anonymous types that PH advocated.) The old term ‘art industry’ was favoured over skønvirke, but the search was on for a more apt term. The critical freethinkers’ journal Kritisk Revy (Critical Revue) printed the term ‘proper industrial art’ on its covers in 1926 as one of the fields it was seeking to promote.

A similar search for an adequate term was seen in Germany and France, where, for example, Le Corbusier wrote about ‘l’art decoratif’ after the Paris exhibition in 1925. He acknowledged the paradox, since his mission was decorative art without thedecoration. After the exhibition Britisk Brugskunst (British Applied Art) in Copenhagen in 1932, ‘brugskunst’ was fielded as a fairly neutral term. It was a translation of ‘decorative’ or ‘applied art’/‘angewandte Kunst’, but we can note that Steen Eiler Rasmussen was not ready to embrace the English word ‘design’, which had otherwise become widely accepted since the establishment of the British Design and Industry Association in 1915. ‘Brukskunst’ was the dominant Norwegian term, featured in the name of both the Norwegian association, founded in 1918, and its journal. The Norwegian names did not change until the 1970s, when the journal became the interior magazine Bonytt (literally Home News), and the professionals split into craft makers and industrial designers. If anyone were to seek to reinstate ‘brugskunst’ as an unsentimental Danish term, the dictionary informs us that it is actually one of the many words introduced by the Danish pioneering scientist H. C. Ørsted in the early 19th century.

In 1947, the term ‘art industry’ was once again mothballed. The Danish Society chose ‘Dansk Kunsthåndværk’ (Danish Arts and Crafts), which also became the long-lived name of the journal. However, in translations, ‘& Industrial Design’ was added, just as the journal clearly covered the full spectrum from industrial manufacturing to unique pieces. Still, there was reluctance to use the English and American term ‘design’ in Danish. The resistance was persistent. Bernadotte & Bjørn, however, did refer to themselves as industrial designers, just as Finn Juhl and Erik Herløw also used the term in Danish as early as around 1950. The majority’s preference for older terms such as ‘kunsthåndværk’ (arts and craft) and ‘møbelkunst’ (furniture art) was rooted in the Klint School’s and the Cabinetmakers’ Guild’s celebration of the collaboration between arts and crafts. Through their involvement, ‘furniture architects’ and craft makers vouched that even mass-produced items possessed value and quality derived from art and craftsmanship. That message proved effective on the international markets, so here, there was no need to relabel the products as design. On the contrary, international buyers wanted an alternative to the stylings of American industrial design.

Perhaps the only term that would garner widespread support from craft makers, designers and architects was ‘formgivning’ (form-giving). Herløw was one of the founders of Selskabet for Industriel Formgivning in 1954. The term highlights the design process more than its outcome, which was also true of skønvirke, the aesthetic treatment of form and material. At the time, the word ‘design’ was not used in that sense. However, even if ‘formgivning’ was chosen as a compromise solution, it never made it into the title of the journal. The Germans and Swedes cut to the bone with the hard-wearing Form as an abstract, common term for the outcome rather than the process.

A return to applied art – and art

During the 1960s, more of the tasks pertained to industrial products and devices, and the field could no longer be contained under the crafts label. In response, there was a return to functionalism and the name Dansk Brugskunst (Danish Applied Art) from 1968. It was intended as a compromise that included both crafts and industrial design. Interestingly, this coincided with a merger of the School of Arts and Crafts with The School of Drawing and Art Industry in 1967. Initially, the common school was called The School of Arts and Crafts and Art Industry, but with School of Applied Art added in parenthesis, see the yearbook 1966/67. In 1973, it was renamed the School of Applied Art but only after six years’ committee work and independence from the Technical School. However, ‘applied’ disappeared from the journal title that same year. Thus, the positions were not at all clear, and several terms were in play over a period of a few years. When Viggo Sten Møller, the former editor of Nyt Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri (New Journal of Art Industry) and the director of The School of Arts and Crafts until 1967, published the first Danish design history in 1970, he chose the title Dansk Kunstindustri (Danish Art Industry).

Thus, ‘brugskunst’ (applied art), did not seem to be a workable compromise but only led to more division. Some wanted to shed any mention of ‘art’, while others missed the crafts element. Danske Kunsthåndværk returned as a stable name in the 1980s but with ongoing debates about the relationship between crafts, industry and design. Not least in connection with the establishment of The Danish Design School in 1990 as a merger of the schools for decorative art and interior design.

Round and round we go

The conceptual history I have outlined above illustrates how names might come under fire during times of change and professional boundary disputes. However, it also illustrates that the terms have been fluid and under continuous negotiation for the past 150 years. And that names can be resilient and gain new meanings when they are revived. It is reasonable to consider the benefit of continuing to invent new names, since so many have been in play, each with its unique history and set of meanings. Moreover, professional traditions and education programmes contain their own historical ideals and concepts, which affect our current debates and positions.

Formkraft is a new name, since we cannot ignore the changing meaning and the disputes about both old and more recent terms. Both ‘design’ and ‘craft’ are international buzzwords that are used far outside their original professional fields and which have even more fluctuating meanings than before. Perhaps, Formkraft will prove more timeless, as ‘form’ has served as a universal concept, especially for the modernists. In both Sweden and Germany, Form is a durable journal name that dates back to, in Sweden, Slöjdföreningen and, in Germany, Werkbund. However, in order to prove sustainable, Formkraft also needs to have contemporary relevance and cover both artistic and problem-solving practices. And ultimately, that depends on content, contributors and readers, not on the title!

Sources

‘An internal conflict of interest in the short-lived publication BID’, poster by Ditte Nylander Jensen, Maria Cecilie Christiansen, Patricia Fie Nielsen, Rikke Lauritsen & Sofie Staal Rundstrøm, University of Southern Denmark, Design Studies, 2019

Mirjam Gelfer-Jørgensen (2020). The joining of the arts: Danish art and design 1880-1910 (trans. René Lauritsen), Strandberg Publishing.

Poul Henningsen (1970). Personlighedens plads (The role of personality) (1979). In Carl Erik Bay & Olav Harsløf (Eds.),Kulturkritik (Vol. 1), Rhodos. (Original work published 1930).

Le Corbusier (1925). L’art décoratif d’aujourd’hui. G. Crès.

Kunsthåndværkerskolens årsskrift 66/67 (School of Arts and Crafts 66/67 yearbook) (1967). Kunsthåndværkerskolen.