The Danish Arts Foundation’s artist-in-residence programme, which accepts applications twice a year, supports opportunities for children and young people to work with professional artists. However, in 2022, just 5.7% of the applications came from designers and makers.

To address this issue, Formkraft asked five makers who have all completed residencies to describe both their positive experiences and the main challenges for makers or designers in the residency programme.

The Utøya massacre as a point of departure

As former head of Albertslund Billedskole (Albertslund Visual Arts School), textile artist Dorte Østergaard Jakobsen has extensive experience with the artist-in-residence programme. In 2013, the Albertslund school organized the residency project ‘Faith, hope and powerlessness’ on the theme of the massacre on Utøya, Norway, which had happened two years earlier. The project was structured as a three-day art workshop for students in years 7, 8 and 9 in collaboration with Danish, Social Studies and History teachers. Prior to the workshop, the students had read the Danish writer Pia Tafdrup’s poem ‘Seven Dresses for Visibility’ from 2011 and the Norwegian writer Nordahl Grieg’s poem ‘To the Youth’ from 1936 in addition to watching films and reading about the Utøya massacre.

What is the best way to get started on an artist-in-residence project?

Ideally, you should seize the initiative yourself, for example by asking the school secretary who teaches arts or craft & design. Other subjects, such as Danish or Maths, can also offer an excellent framework for a ceramicist or a furniture designer, as you can use measurements and geometry and construct objects in the form of cylinders or cubes. The key is to find a teacher who thinks it would be fun. Many teachers are delighted to take you up on the offer!

We organized our residency projects as three-day courses. That duration was feasible for the schools, and in our experience, it has a good effect. On day one, the students get started. Day two is a day of complete immersion. On day three, it’s time to wrap up, review and tidy up, and once all the groups have completed a three-day course, the students help hang the pieces in an exhibition.

How do you structure you collaboration with the schoolteachers?

The teachers prepared the students using the texts we sent them. But otherwise, we presented the teachers with a package deal. We prepared a detailed description of the process, which we sent to the teachers, so they knew what was going to happen. The teachers were in charge of preparations at the school, because it was important that the students came into the course with an interest in the process.

First, we had the students shape three small clay figurines on the themes of faith, hope and powerlessness. We had prepped the clay and utensils, and after a brief introduction, we really just let them dive in. The results were awesome. Powerful and great. Sometimes, painting can be difficult. But by starting with a three-dimensional task, we found it was easier to engage both boys and girls. That is a method we have used many times.

Subsequently, each student sketched and painted a piece that expressed the feelings the Utøya massacre had sparked in them, with inspiration from the two poems. After the course, the figurines and paintings were exhibited at Albertslund Town Hall.

Do you have any experiences you would like to pass on to others who might be considering applying to the artist-in-residence programme?

It’s nice to team up with a partner, as it’s a demanding process. It can be helpful to have a partner from a different artistic discipline, so that you cover a wider span of knowledge and approaches.

Another point is that we often held artist-in-residence projects for the older students in autumn, because they have exams in spring, although it also shouldn’t be too close to the start of the school year either.

It is always important to mark the end of the project with an exhibition, a performance or other type of event. We often have the Mayor of Albertslund and a member of the municipality’s Culture Committee to give a speech at the opening of the exhibition, and we invite the local print and TV media.

The municipality as the initiator

Ceramicist Tove Skov Larsen and textile artist Lise Frølund have done several artist-in-residence projects together.

In 2022, Tove Skov Larsen was contacted by Middelfart Municipality at the recommendation of Clay Museum of Ceramic Art Denmark. The municipality wanted to do an artist-in-residence project, and Tove Skov Larsen invited weaver Lise Frølund to take part.

The municipality wrote the application and covered the costs for materials and transport for two parallel artist-in-residence projects at Vestre School (year 3) and Båring School (years 4 and 5).

What were your methodological considerations for the project?

The municipality’s underlying vision was ‘From Child of Middelfart to Citizen of the World’. We included that in our work. We used clay from the town of Middelfart and glazes made from local clay and seashells. We also used local plants, such as stinging nettles, for textile dyeing and weaving. The students thought that was fun.

Our educational goal was for the children to learn about patterns and repetition, for example the repetition of a pattern in different glazes.

Does it make a difference that the Danish Arts Foundation requires you to place priority on the process, not on the end result?

Yes. It is important to keep in mind from the beginning that your focus is on process. The students really wanted to take the objects home, but we had defined, ahead of time, that the objects belonged to the schools, not the students, and that it would be up to the schools how to use the output of the project. However, at the exhibition opening, the students were given a small ceramic pendant to take home, which featured most of the ceramic processes, on a string made of stinging-nettle fibres.

Would you recommend others to engage in an artist-in-residence course?

Craft is perfect for a residency project because process is such a big part of it; different kinds of processes, too.

In every regard, it has been helpful to have a partner, and our approaches have been quite different. You have to be prepared for an artist-in-residence project to take up a lot of your mental time, but the experience also contributed to our own development, in part because we did parallel processes with two groups and were able to evaluate our own process along the way.

Artistic upcycling of textiles

Tapestry weaver Sanne Ransby recently completed an artist-in-residence project with students from Århus Designskole/Kompetencehuset (Århus Design School/Competency House), which is a preparatory school for creative education programmes. She based the first part on one-to-two-day workshops totalling seven school days in spring 2022, while the second part, in autumn 2022, took place over five consecutive school days. The theme of the project was artistic upcycling of uniforms, sheets and bed linen from the hospital laundry facility midtVask Hospitalsvaskeri and involved students aged 18 to 25.

How was the artist-in-residence project arranged?

I was contacted by the school director, who was looking for a textile artist. The school’s own teachers had a more utilitarian approach to textiles: fashion, design, architecture. By inviting me in, they were able to offer a wider range of approaches to the combination of recycling and design, and through the projects, the students acquired a different perspective on their own work.

The idea was that I would ‘drop a bomb’ to pull the students away from their computer screens in a project that took a more analogue and explorative artistic approach.

We chose to meet once a month during the spring project. In the autumn project, we joined the days together into a longer process. The latter approach clearly worked better.

We concluded the two projects with very different types of evaluation. In spring, the students’ photos and texts were turned into a booklet prepared by the graphic design students. In autumn, we concluded the project with an exhibition and a presentation for the whole school.

How did the students feel about the experience?

Generally, the design students had an approach that aimed at solving a problem. In this project, they were asked to engage in physical explorations, for example of colour gradation on the bed sheets or in the form of weaving. In another task, they took a spatial approach – either digitally or in a physical model – which produced some really interesting results.

The students generally had positive feedback. Many of them moved outside their comfort zone and discovered that they were able to make something with their hands that took on a physical presence and expression in a short amount of time.

Would you consider applying for another artist-in-residence project?

Yes. I also learned from it myself, including gaining insight into different types of working process and approaches. I previously taught preschoolers and adults, so I also gained experience working with a different age group.

Clay shapes words in reception class

Ceramicist Alikka Garder Petersen is currently doing the artist-in-residence project ‘Shaped in clay and words’ at Rådmandsgade School in Copenhagen together with jewellery artist Signe Bendixen Madsen. In this project, both artists work with ceramics. The students are refugee and immigrant children in the school’s reception class, aged 13–16. They do not speak Danish, some have a little English, and they do not have a common language. The project lasts four months total, with one to two days a week, and at the time of writing, it is approximately at the half-way mark.

How did you approach the application process?

I knew one of the Danish teachers from a different project and contacted her about a year ago. The project is part of Cerama’s (The specialist glass and ceramics supplies shop) project ’Hands for Life’, which offers ceramics-related activities for at-risk citizens, so Cerama contributed to the funding.

We agreed to make this a longer project in order to help the students develop a common language and provide the time for a calm, immersive process.

Through ceramics, they can express themselves without words, and at the same time, they learn Danish. The teacher who teaches Danish as a second language has a great energy and attitude to using other approaches besides buckling down at the your desk to learn a language.

We met about five times before submitting the application to the Danish Arts Foundation in order to specify the activities and to define our own and the teachers’ roles in these activities. Afterwards, I wrote the application together with the Danish teacher.

Did the teachers welcome you in?

Yes, they really did. It’s great to have them involved in this. We don’t need to worry about resolving conflicts, and the teachers have been good at using the other Danish lessons to prepare topics that connect with what we’re doing.

How have the students in the reception class benefited from the artist-in-residence project so far?

Through art, the students are able to work with bodily, tactile and physical aspects.

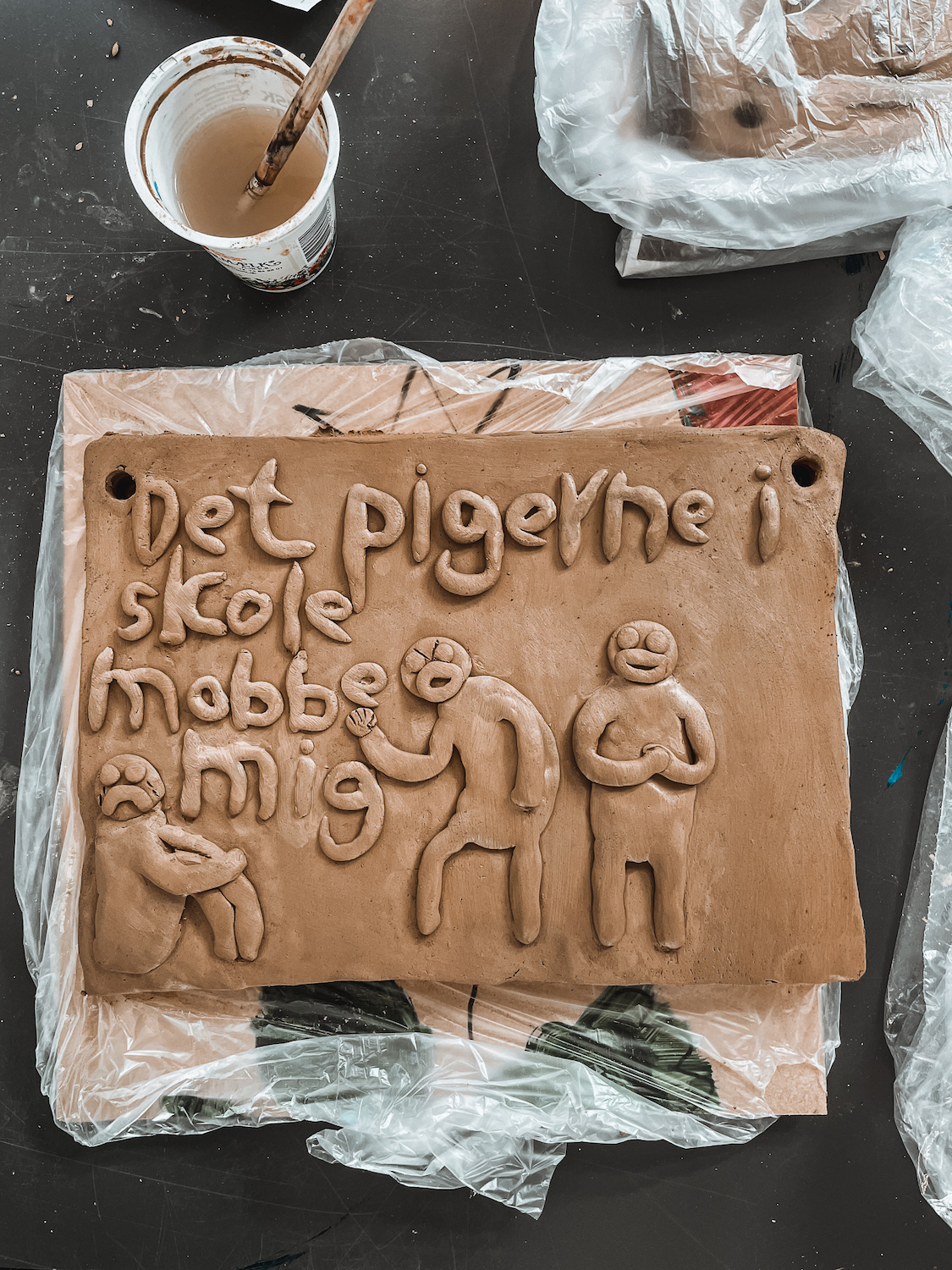

We have now reached the final part of the project; in this part, the students are going to make three reliefs that address an event or an experience that changed them. A turning point. The reliefs will show the time before, during and after the event, respectively. As part of this process, we visited Thorvaldsen’s Museum to look at friezes and reliefs.

One of the key points of the project was teaching the children that it’s okay to make mistakes. That when you make a sketch, it’s not a failure; you’re trying something out and working something out. To some, that has been a cultural shift, because they haven’t been used to the idea of trial and error or allowing their personality to shine through.

We conclude the project with an exhibition of the reliefs, and finally, the Danish teacher and I write an article for the Folkeskolen journal and for Cerama’s website.

Would you consider applying for another artist-in-residence project?

If I were to apply again, I would make sure to have the necessary time to prepare. Both before and during the project. We have needed to make adjustments throughout. I have extensive experience with teaching, but this is different because the children don’t speak Danish.

Hvilket udbytte har modtageklassernes elever fået gennem huskunstnerforløbet ind til nu?

Gennem kunsten får eleverne arbejdet med det kropslige, det taktile og det fysiske.

Vi er nu nået til den sidste del af projektet, hvor eleverne skal lave tre relieffer, der skal omhandle en begivenhed, som har forandret dem. Et turning point. Reliefferne skal vise før, under og efter begivenheden. Så der har vi været på Thorvaldsens Museum for at se på friser og relieffer.

Som noget af det vigtigste i projektet, har vi arbejdet med, at det er ok at fejle. At når man laver skitser, er det ikke en fejl, men man prøver noget af og arbejder sig ind på noget. For nogle har det været en kulturændring, fordi de ikke har været vant til, at man kan prøve sig frem og lade sin personlighed skinne igennem.

Vi afslutter forløbet med en udstilling af relieffet, og til sidst skriver jeg og dansklæreren en artikel til Folkeskolen og til Ceramas hjemmeside.

Vil du overveje at søge huskunstnerordningen igen?

Hvis jeg skal søge igen, så skal jeg have mere fokus på forberedelsestid. Både før og under. Vi har hele tiden haft behov for at justere. Jeg har god erfaring med undervisning, men det her er noget andet, fordi børnene ikke kan dansk.

Advice for artists-in-residence

Team up with a partner – possibly someone from a different artistic discipline.

Include time for preparation, both before and during the artist-in-residence project in your salary.

Consider whether to plan and apply for a longer project that allows for a more in-depth experience.

Remember to include costs for materials and transport as part of the host’s co-funding.

Prioritize a good conclusion to the project, for example an exhibition opening or press coverage.

Theme: Artist-in-residence

Formkraft will examine why artist in-residence partnerships between organizations and makers/designers are not more common.

What challenges do practising makers and designers face once they have been approved for a residency? How is the partnership between the maker/designer and the host organization established? What do makers and designers think of the application process? And how do the approved projects benefit makers and designers, host organizations and the children and young people they work with?

More knowledge in the Archive

Search for relevant knowledge in the Archive on Formkraft and find several articles about craft and design. Most of the articles have an English translation.