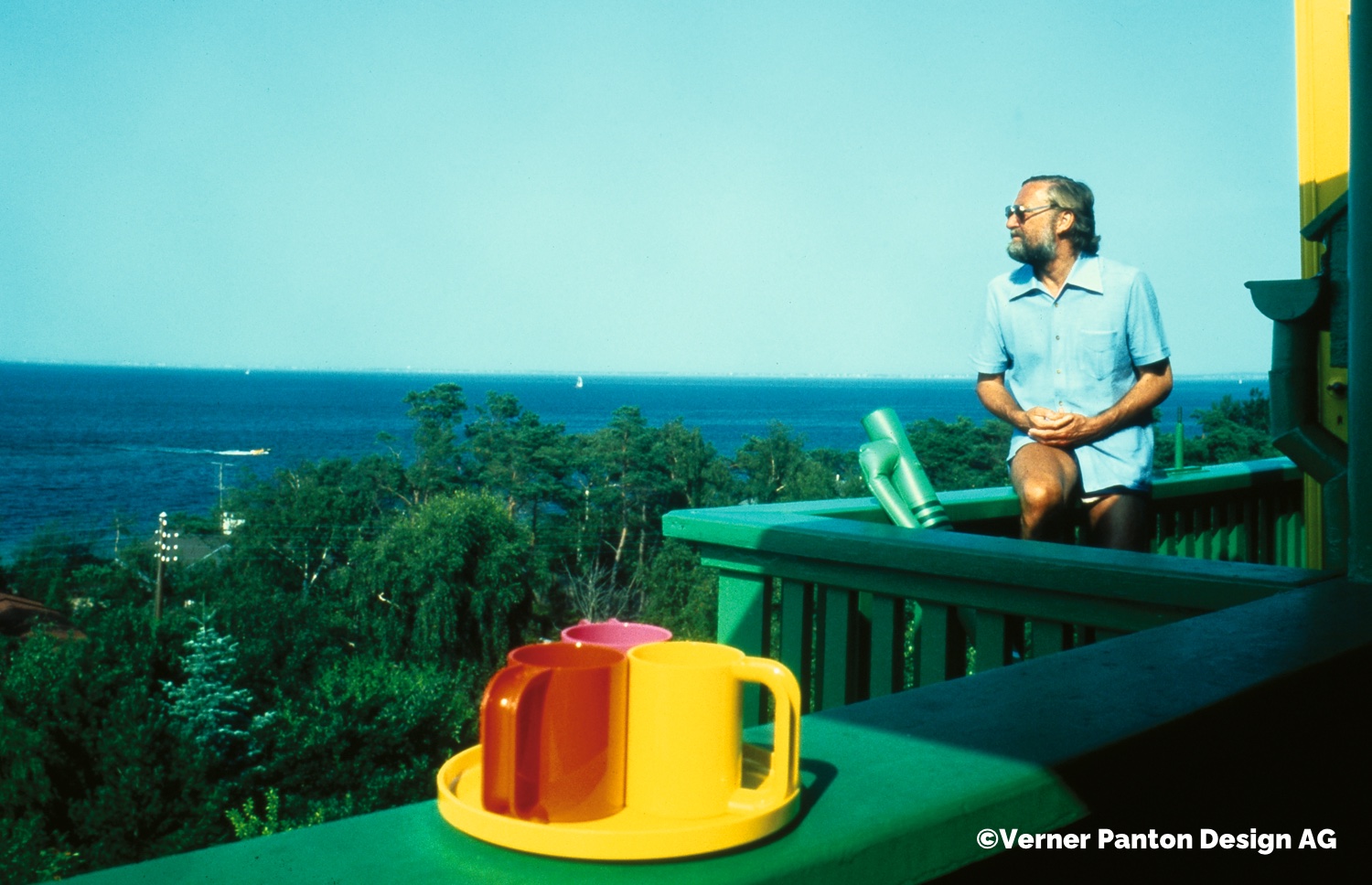

For more than five decades, Verner Panton came up with countless designs that still provoke, stimulate and shock audiences today with their visionary, humorous riot of forms and colours. He called himself an inventor, and when asked which of his designs he was most fond of, his answer came without hesitation: The one I’ll do tomorrow. (S.S., 1996) For Panton, the key thing was the idea and the sheer joy of inventing something new – of suddenly seeing the world differently. Panton stated that he would rather carry out a less-than-successful experiment than some nice, neat indifference (Matz, 1995). In particular, he emphasised that he had no wish to encroach on the territory of Kaare Klint, Hans J. Wegner and Børge Mogensen, who had already created well-made, successful furniture (Helles, 1980, pp. 62-65).

About the exhibition

Verner Panton – Colouring a New World (Farver en ny verden)

Trapholt: 30.09.2021-14.08.2022.

Spanning five decades of colourful designs, the exhibition presents furniture, lamps and textiles, but also sensuous immersive environments such as Fantasy Landscape

According to Panton himself, his fascination with devising, developing and realising ideas is opposed to that of ‘designing’, which he describes as a process that has already been thought through in advance. Accordingly, he does not let himself dwell on the enthusiasm of his many designs.

Verner Panton – Colouring a New World is the title of Trapholt’s 2021-22 exhibition about Verner Panton. Presenting Panton’s visionary thoughts and methods, the exhibition speaks into our Covid-19 times of crisis where a renewed collective awareness is pushing society in a new direction.

Can we use Panton’s unconventional approach to design as a source of inspiration in our efforts to rethink our social lives? Can we learn something from the colourful designer’s ideas about the sensing body and the unconscious mind? And does Panton have the answer to what so-called ‘good taste’ is?

Verner Panton ranks among the great Danish designers who became significant exponents and arbiters of how Danes view and think about aesthetics, design and function. He set an agenda that defined – and still defines – the collective understanding of what is considered good taste. Panton emerged as the antithesis of the rigor of functionalism with his imaginative and colourful approach to design.

His aim of linking the sensing human being with physical spaces filled with colour, shapes, materials, sounds and scents marked a new departure, and prompted us to rephrase Panton’s question: Is good taste also a feeling of well-being? (Panton, 1980). This article will explore the question above in order to examine and answer the question whether good taste is a feeling of well-being.

My Design Philosophy

In the spring of 1980, Panton gave a manifesto-like speech for an industry event in Vienna, arranged by BÖIA – Bund Österreichischer Innenarchitektur. He later gave the speech at Møbelmessen (the Furniture Fair) at Bella Center in Copenhagen in 1987 and again the following year at the opening of the international furniture and interiors fair in Cologne Germany in 1988. That same year he appeared in front of a large group of design critics who had come to Denmark from all over the world (Rémy-Jensen, 1988).

A shortened version of the speech was published in 1989 on the occasion of fellow architect and designer Hans J. Wegner’s 75th birthday, presenting Panton as a playful, energetic designer who mischievously challenged the established world of furniture production (Panton, 1980).

In 1995, the speech was published in the German magazine BÜROszene as a portrait of Verner Panton, headlined meine Design-Philosophie (My Design Philosophy) (Blaser, 1995). In this publication, the speech is reproduced in its full length and in the original language (Danish) titled Min Designfilosofi; meaning ‘My Design Philosophy’.

In his speech, Panton asks rhetorical questions about economics, power, sensuous living, nature and culture – offering up a kind of manifesto that covers five realms: the sociological, the economic, the educational, the phenomenological and the biological.

The key element in his speech is Panton’s interpretation of taste and well-being, where he rhetorically asks the question: can one develop a theory of feeling good? (Panton, 1980)

Taking his point of departure in the idea of good taste, he asks in equally rhetorical fashion:

have you noticed that people’s taste changes concurrently with their level of prosperity?

the more people earn the more conservative they become?

Panton thus posits a possible connection between income and conservatism, but also calls for an answer to whether taste is determined by cultural or biological factors:

is taste a natural – innate sense or an acquired one?

is there such a thing as ‘good taste’?

Panton wants to find the as-yet unproven formula of good taste. Accordingly, he asks:

is it possible to process and define good taste in a scientific manner, and thus to teach it and learn it?

The answers regarding the matter of good taste must be found in Panton’s rhetorical questions about well-being. Based on the phenomenology of how we physically experience the world, he asks:

isn’t sex the ultimate form of well-being for most people?

is well-being not good music – a pleasant scent – good food and drink – being with nice people – good entertainment?

Panton also seeks answers to whether well-being is a sensation that lurks in our subconscious mind – he asks:

is well-being rather the observation of pleasant proportions – good combinations of colour and material – of pleasant daylight and appealing evening lighting?

The speech is a mosaic of Panton’s many public statements throughout his career, compiled and written up by Rina Troxler. She was Panton’s secretary and always transcribed Panton’s speeches, first in Danish, then translated into German and English, based on many small scraps of paper carrying his notes, which he always kept at hand so that any glimmers of new ideas could be kept from disappearing.

Panton’s audience usually constituted a mixture of furniture manufacturers and design communicators in the form of journalists and photographers. On the opening day of the furniture fair at Bella Center in 1987, he acted as the official speaker at the press lunch, much to the delight of the two hundred media people assembled there. Beginning his speech in a joking fashion, he included a warning to the audience:

I am going to speak for about 10 minutes in poor German –

I’ll hurry –

(…)

can questions also answer questions?

I’m asking –

In terms of genre, this speech is an official opening speech that caters to its audience through meta-communication, specifically pointing out how it is structured (Lund, 2020). According to the head of the Centre of Rhetoric, associate professor and Ph.D. Marie Lund, official speeches have, since the mid-1960s, been characterised by the fact that they, like the general fashion in modern rhetorics, have become more personal in their approach and use everyday language (Lund, 2020).

The present speech is constructed as a long chain of philosophical and personal questions that let Panton indirectly explain his views, which are reminiscent of an artistic manifesto. The speech is in itself a performative act, one where Panton’s inner and outer motivations struggle within the parameters of, but also in opposition to, design culture’s basic narratives and norms (Hansen & Staunsager, 2015). Paradoxically, Panton concludes his speech by stating that no questions should be asked.

In his speech, Panton questions the idea of so-called good taste and the feeling of well-being. Two concepts that he challenges with rhetorical questions according to the Socratic method, so named after the critical dialectic of the Greek philosopher Socrates (d. 399 BCE). This is to say that the questions presented in the speech become a form of cooperative dialogue that stimulates critical thinking on one’s own terms.

Taste: a culturally conditioned phenomenon

Verner Panton inquires into the idea of so-called good taste:

isn’t good taste often just plain boring?

For Panton, good taste creates the framework for how we experience, perceive and sense the world. He understands the concept of taste through a prism of sociology, economics and education, the latter in a broad sense that includes general refinement, civilisation and personal growth. Regarding the realms of sociology and economics (socioeconomic factors), he specifically asks:

are people’s tastes and demands governed by their income?

According to Panton, economic and financial progress leads to a creative decline (Hartung, 1979). He felt this when, towards the end of his career, he caught himself thinking about whether his designs would sell – an aspect he had never given a second thought before (Victors, 1970). According to Panton, financial progress brings a sense of security and stagnation in its wake; only uncertainty nourishes creative progress (Panton, 1992).

Today, the concept of taste is generally based on everyday assessments and evaluations that can be discussed normatively as judgements of good or bad taste. When examining Panton’s approach to the concept of taste, the ideas of French sociologist and anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) offers a useful starting point and theoretical approach when seeking to understand and apply perspective on Panton’s worldview. Bourdieu contemplates taste as a social construct. In his magnum opus La Distinction from 1979, he opines and documents that taste should be considered in a cultural-sociological light because it is subjective. Bourdieu thus provides an empirically grounded theory for the analysis of taste. According to him, taste is neither essential nor individual, but relational and socially conditioned. That is, taste is not biological, but something that is constructed as a result of our social class – both the one we belong to and the one we aspire to.

In line with Panton, Bourdieu also argues that taste depends on our financial position in society. Bourdieu’s definition of taste is based on overtly articulated preferences (Bourdieu, 1986). This means that we set ourselves apart from others by expressing what we do not like. Accordingly, the idea of taste is very much about distaste. A key quote by Bourdieu specifically points out that when someone makes a taste judgment and classifies others as having good or bad taste, that person also classifies themselves.

Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier (Bourdieu, 1986).

It should be noted that Bourdieu and Panton were much of the same age: La Distinction was published in 1979, and Panton gave his manifesto speech for the first time the following year, in 1980. In his speech, it is clear that Panton’s interest in the social sciences was inspired by and leaning against the currents of the time, on which Bourdieu’s social constructivist ideas are also based.

Considering the ideas of education, culture and acquired abilities, Panton poses a similarly rhetorical question in relation to taste:

is so-called ‘good’ taste something acquired, something you learn and hold on to out of firm convictions, or is it just something you thoughtlessly imitate?

Through colours, Panton teaches us that good taste is culturally determined. He successfully instils a sense that his designs are certainly not indifferent, and so we have to respond and take a stand on them. Colours become an active choice, a deliberate action. In line with Bourdieu’s definition, taste depends on our actions and consumption, which speak volumes about the lifestyle and social position we subscribe to. Taste is conditioned and governed by social class and capital.

Panton believed that the formative influence of primary school and its accepted notions of good taste are particularly to blame for strapping us into a straitjacket that is unnatural, thereby failing to provide us with the courage to embrace colour. Panton concludes that our fear of colour arises during our upbringing – in kindergarten, young children learn to love and use colours. But as children get older, they become afraid of colours because primary school teaches them that a riotous use of colour is in poor taste (Panton, 1991, 2nd. edition 1997).

Accordingly, he argues that instead primary schools should nurture and develop children and teach them about colour. Panton himself studied colour psychology at Psykologisk Laboratorium in Copenhagen under the psychologist Martin Johansen in the late 1950s, learning about the psychological influence of colour and space. This made him aware of how colour affects our mood and ability to work.

As a result, Panton emphasises colour over form and function, fuelled by a vision for the home of the future, a home filled with an array of colours akin to fireworks (Agersted, 1969). In 1991, Panton published the book Lidt om Farver (Notes on Colour) about human perception of colour and the significance of colour in art. In the book, he writes about how the use of colour is a deliberate act that expresses moods, visions and dreams (Panton, 1991, 2nd edition 1997).

Colours send a message of sheer joy, an aspect far more important than so-called good taste. Limiting the use of colour in the name of good taste is tantamount to deliberately shutting off one’s ability to fully sense and experience the world (Rémy-Jensen, 1988).

Well-being: conditioned by biology

At the same level with the concept of good taste, Panton presents and articulates another central concept: that of well-being. The biological aspect of well-being should be understood as an innate trait which prompts natural responses when we are in contact with the outside world.

Regarding the feeling of well-being, Verner Panton asks:

can colours cause well-being?

The manufacturers always made the prototypes shape in white, and that gave Verner Panton a good opportunity not to be distracted by the colour. (Erup, 1992). For him, well-being was a feeling and a subconscious act. Through colour, he can evoke specific physical sensations and experiences, and he speaks of the concept of well-being through a prism of phenomenology and biology. On the issue of well-being, he asks the rhetorical question:

does one seek well-being with furniture?

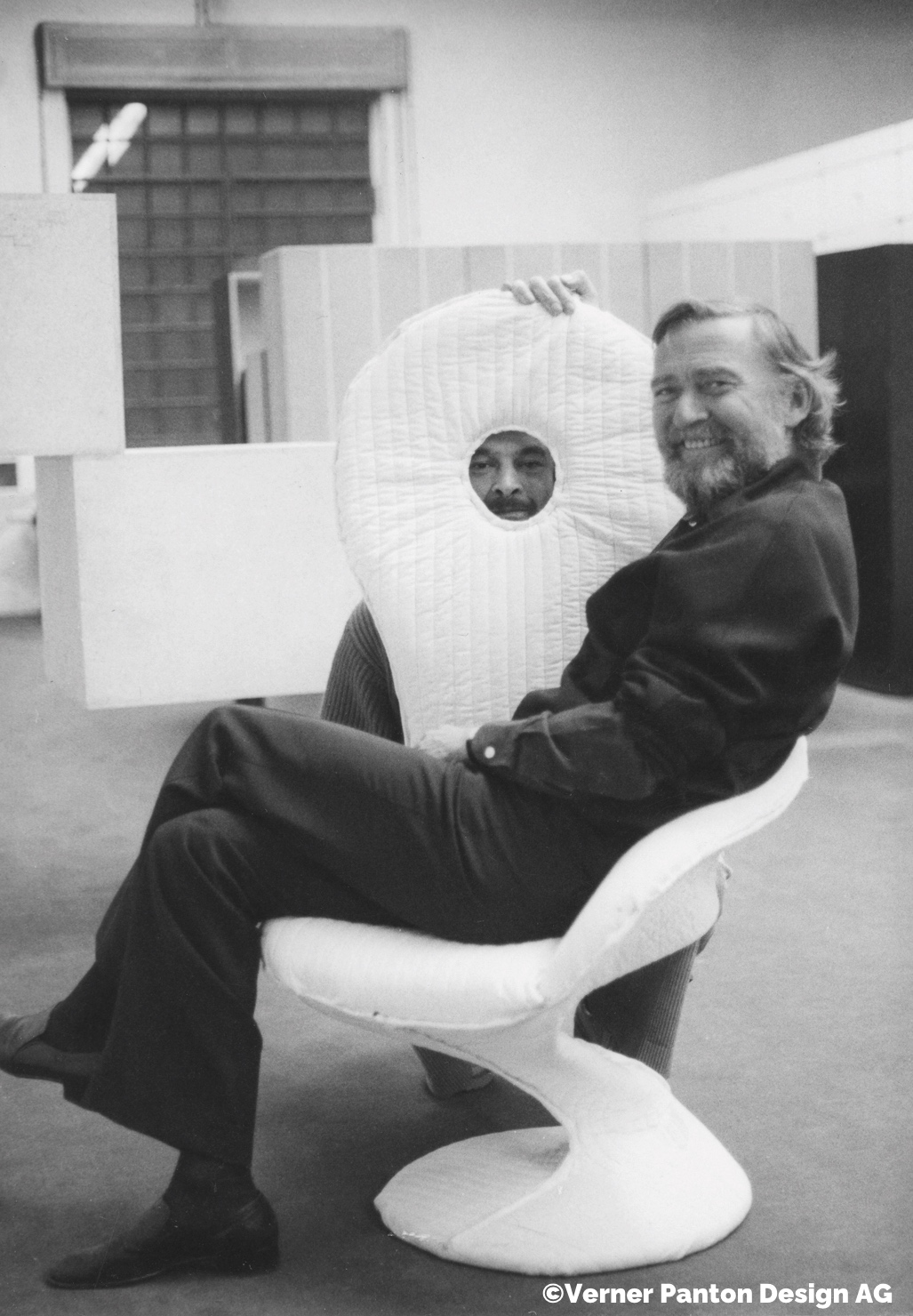

Keenly interested in the idea of sitting better in a purely physical sense, Panton was fascinated by the idea of sitting in a saddle on a horse because it moves naturally (Erup, 1992). All of Panton’s designs are underpinned by a specific idea and specific knowledge, and his designs for seating in particular are based on his firm belief that human beings are not built to sit still. With his many designs, he expands the scope of various furniture types in terms of scale and concept, but at the same time he responds to human proportions, constructing his furniture with ergonomics and movement in mind. Panton’s furniture designs tilt, swing and sway, keeping the body moving instead of locking it in place (Matz, 1995).

Panton’s approach to the concept of well-being can be usefully considered in light of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s (1889-1976) seminal text Bauen Wohnen Denken (Building, Dwelling, Thinking) from 1951, in which he develops a kind of metaphysics of place, using phenomenological thinking to argue that the way we build and the way we live has existential impact on our well-being. According to Heidegger, our own existence and presence does something to the house we live in and the furniture with which we surround ourselves – but the house and the furniture also do something to us in turn (Heidegger, 2000). For Panton, this is all about how a planned environment only takes on real value when it is used by humans (Lykten, 2019, p. 98). In keeping with Heidegger’s theoretical starting point, Panton presents us with furniture – with designs for living – that can be experienced on several levels at the same time. Our everyday familiarity with such furniture is one aspect; our deliberate choice of it and our decision to use it is another. Looking to Heidegger, one can forget how one lives, yet still do it. Looking to Panton, one can forget to move, yet still do it (in his furniture).

Panton takes his point of departure in phenomenology and biology as opposite numbers affiliated with subjective experience and objective knowledge when he rhetorically asks:

is well-being an intellectual or an emotional experience?

in the woods – on the beach – in the sun – when it snows, one often feels comfortable – but in a room, where everything is influenced by human hands, is this not rather more difficult?

Panton designed rooms as totalities, as holistic spaces in which colour first, and light second, were crucial to their atmosphere. Colours were used deliberately to evoke specific emotional experiences. Panton argued that a new piece of furniture for the home is only truly experienced visually for four days. After this point, you may well see the piece, but really only register its presence, whereas you constantly notice whether or not you feel comfortable with it. Accordingly, any new piece of furniture must be chosen on the basis of an emotional aesthetic in order to take our well-being into account (Victors, 1970).

The renowned Danish furniture designer and professor of architecture Kaare Klint (1888-1954) applied a functionalist approach to furniture design in his endeavour to create furniture that suited the human body according to two main factors: the body’s dimensions and its movements. Klint took an analytical approach to measuring size in relation to creating comfortable and functional furniture for the general public.

I remember a dining room where, in pursuit of harmony, all the furniture was, despite serving very different functions, kept at the same height: that of the table top. The result was not harmonious; it felt as if one’s body was on the rack (Klint, 1930).

In this quote, Klint points towards the physical, bodily experience; an aspect that Panton also insists upon in his approach to well-being being tied to the individual’s physical sensation. Klint’s furniture programme includes instructions for storage and regulations on usage, pointing towards a standardisation of furniture in keeping with a functionalist furniture philosophy. However, designers still needed scope and opportunities for development in different directions that did not have to abandon the fundamental idea of functionalism, but might perhaps even expand the concept to encompass both material values and emotional functions (Fisker, 1950). This is in line with Panton’s work, Heidegger’s theory and Klint’s narrative about how we as humans are not only socially constructed, but also shaped by the spaces and objects with which we surround ourselves. According to Professor of Health Services Research, Regner Birkelund, phenomenology can be seen as a response to positivist ideologies and reductionist theories and outlooks on life. He argues that our perception of sensory impressions from our surroundings has existential significance for us in terms of cognition, in shaping who we are, and in terms of our health (Birkelund, 2013). By means of aesthetic impressions, Panton wishes to stimulate our eyes, ears, body and mind through his designs.

Well-being before taste

With a keen eye for economics, power, sensuousness, nature and culture, the manifesto speech clearly shows that Verner Panton was driven by curiosity. Panton wanted to promote greater awareness of our social life and culture. He questioned the concepts of taste and well-being in an attempt to arrive at a theory of feeling good. In his speech, Panton attacks the concept of good taste as being reactive and culturally conditioned, and he also presents the feeling of well-being as a counterpart to good taste, one that engages positively with the sensing body and the subconscious mind. Well-being becomes a source of activism and a means of ruling taste. Therefore, well-being is the key concept for anyone wishing to understand Panton’s starting point.

For Panton, the concept of taste should be understood as being both a judgement of taste and an aesthetic sensibility. Taste thus becomes a socially mediated act. Panton defines the concept of well-being as a physical, bodily sensation, which makes well-being a subconscious act, free from social filters and thus more honest. From this it can be concluded that for Panton, good taste is conditioned by a well-being that is physical in nature, governed by biology.

Verner Panton – Colouring a New World

Trapholt’s 2021-22 exhibition about Verner Panton offers insight into Panton’s aesthetics, creativity and thinking. In so doing, the show gives topical relevance to Panton’s notions about well-being as a starting point for aesthetic expression. The exhibition is curated thematically in selected cases in context with the present speech. Simply put, each case is linked to a quote by Verner Panton from the manifesto speech. The exhibition investigates Panton’s approach to creativity and social life and how it might apply to our times of the Covid-19 crises, where culture and well-being are highly relevant parameters in the ongoing development of our public society, which may be heading in a new direction.

Panton takes an activist approach to circumventing the social filters of good taste. Throughout his long career, he addressed well-being in his projects, which can be divided into two themed categories:

- LIGHT AND COLOUR

- FUTURE HOMES

What follows below are three examples where Panton worked both rhetorically and practically with well-being in his projects. All examples are presented and recreated, in whole or in part, as part of the exhibition at Trapholt 2021-22.

LIGHT AND COLOUR

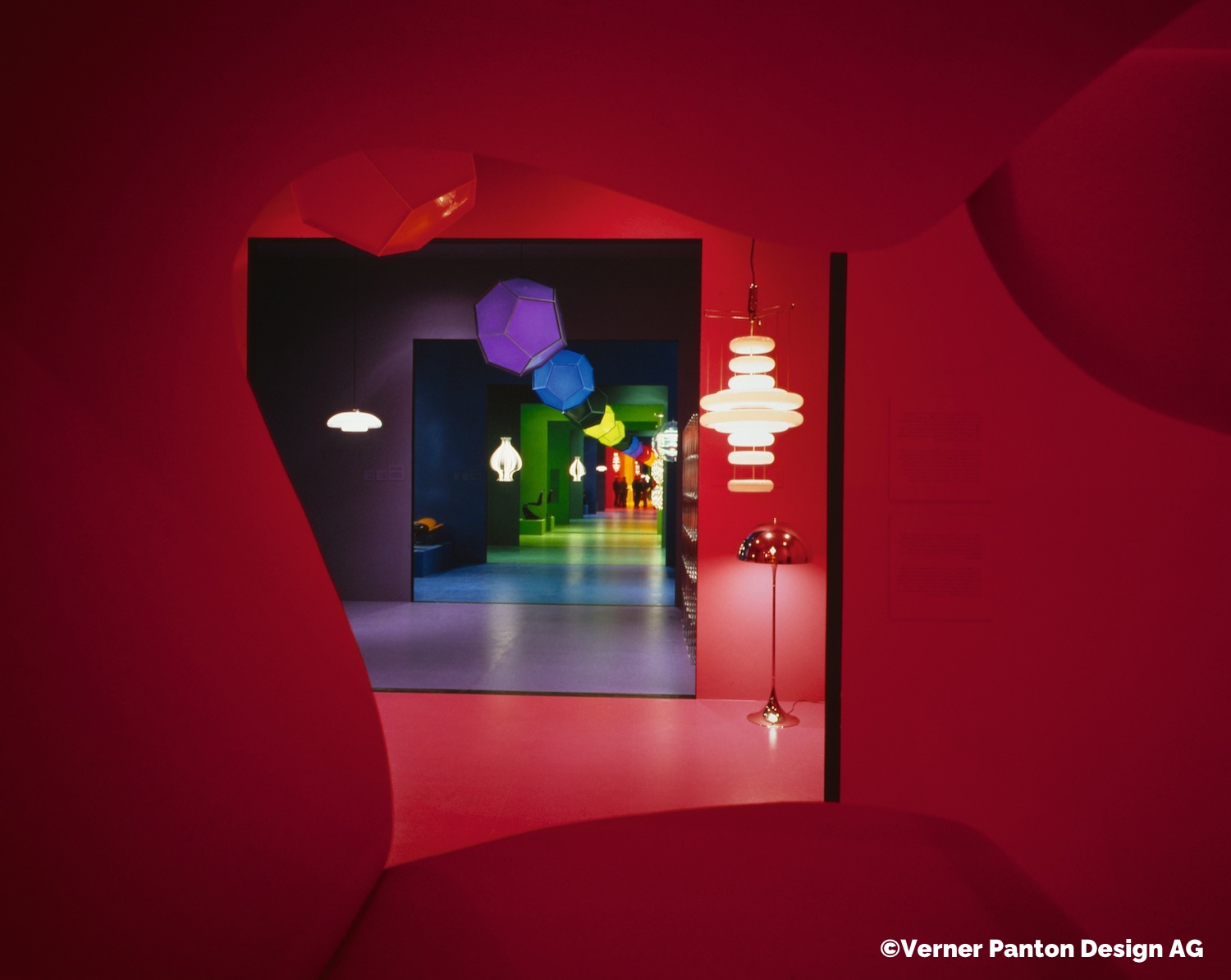

Light and Colour – an installation by Verner Panton (1998)

Verner Panton asks:

is well-being rather the observation of pleasant proportions – good combinations of colour and materials – of pleasant daylight and appealing evening lighting?

The installation Lyset og Farven (Light and Colour) created for Trapholt in 1998 was meticulously curated by Verner Panton himself. It shows a selection of his outstanding designs of furniture and lamps spanning 50 years. The installation consist of eight spaces, each with its own signature colour conveying a distinctive bodily sensation and, thus, sense of well-being as you transition from one colour to the next. Enthrallingly, the installation bears out the words that Panton himself used to describe his universe: ‘I do not and never have done what everyone else does’ (Holm, 1999).

In this installation, visitors can explore how Panton engages, in concrete terms, with his theoretical resistance against predominant notions of taste. Ultimately, this dynamic is the cause of that special atmosphere which pervades Panton’s world of colour and light.

FUTURE HOMES

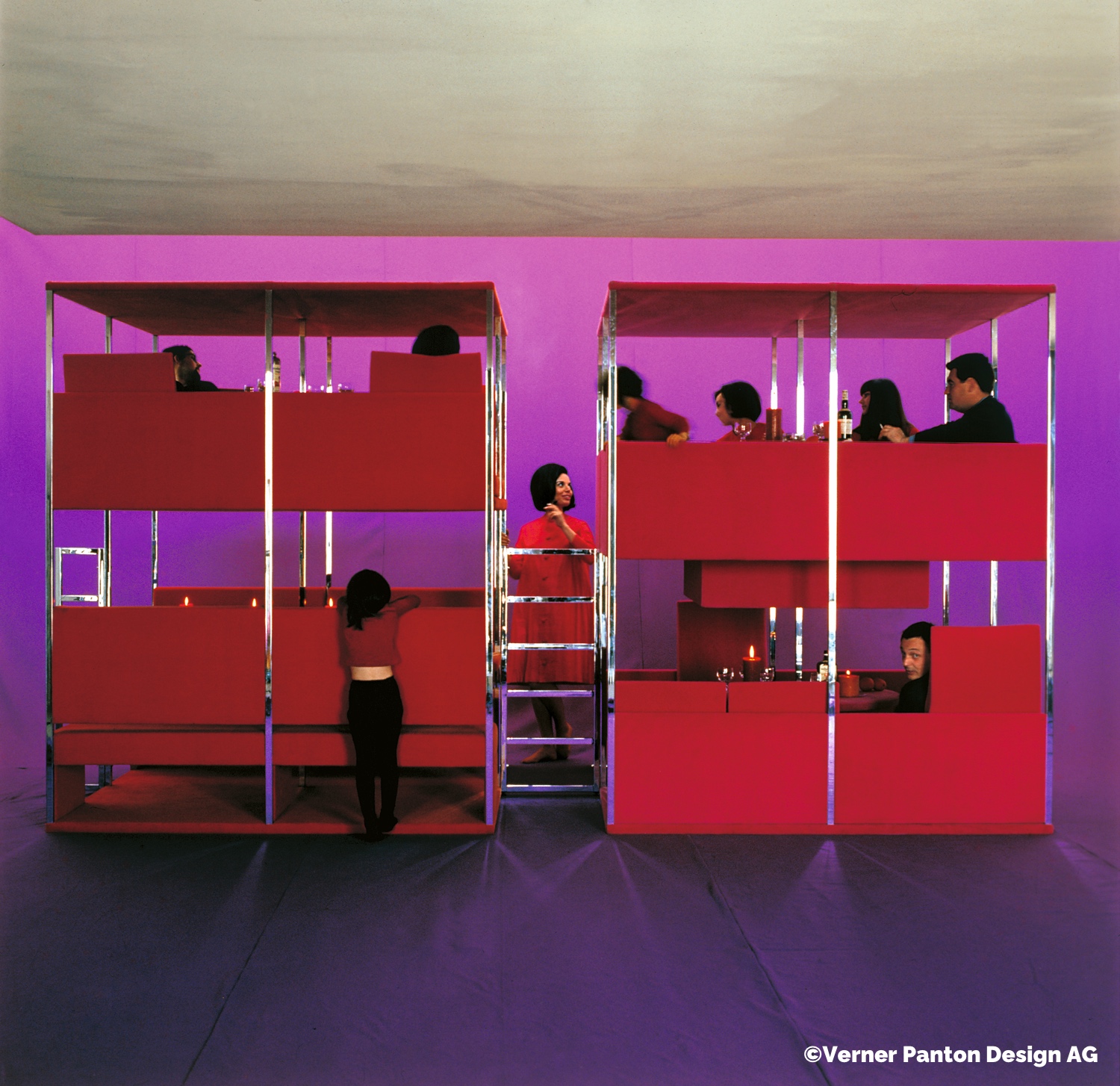

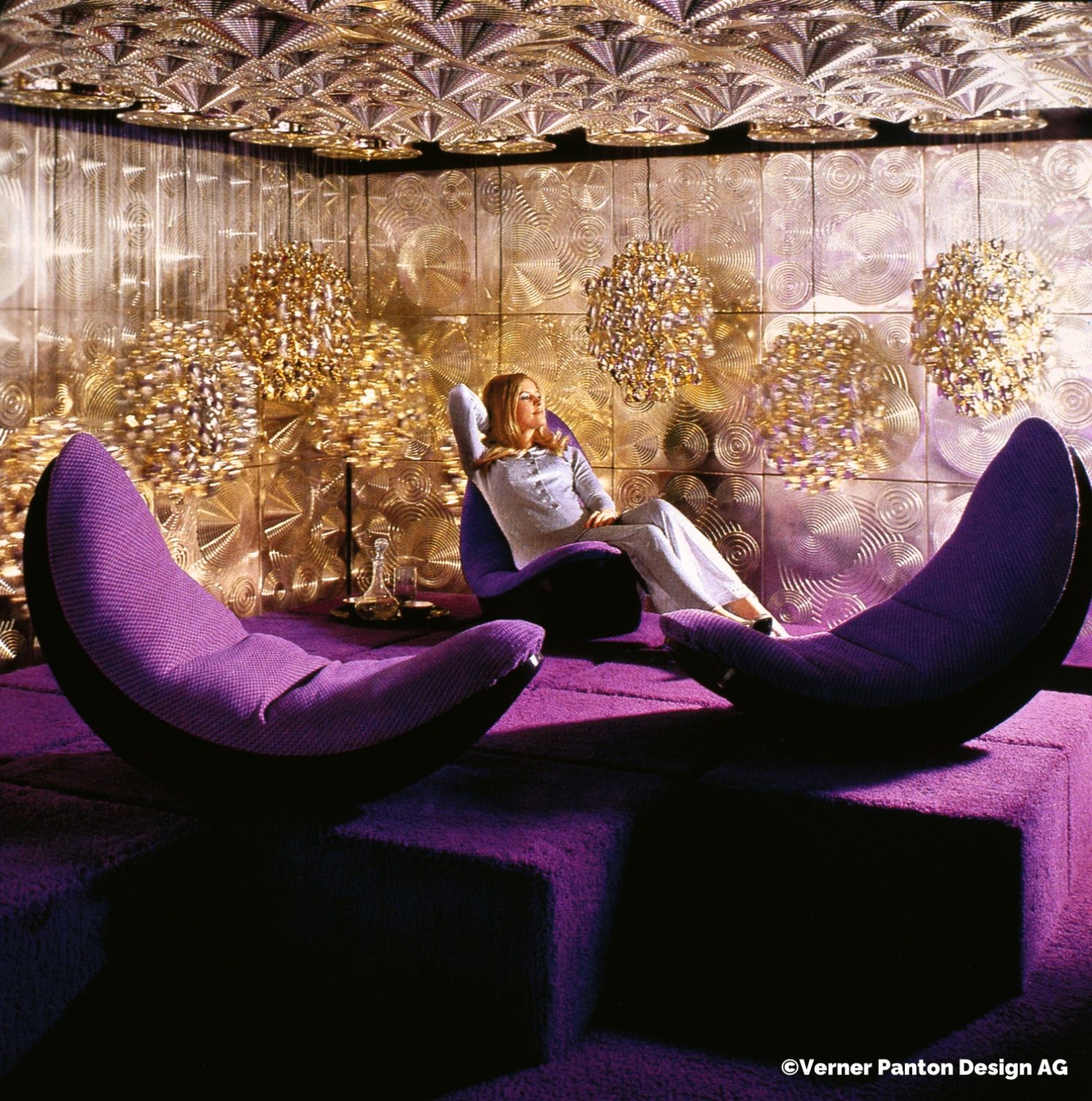

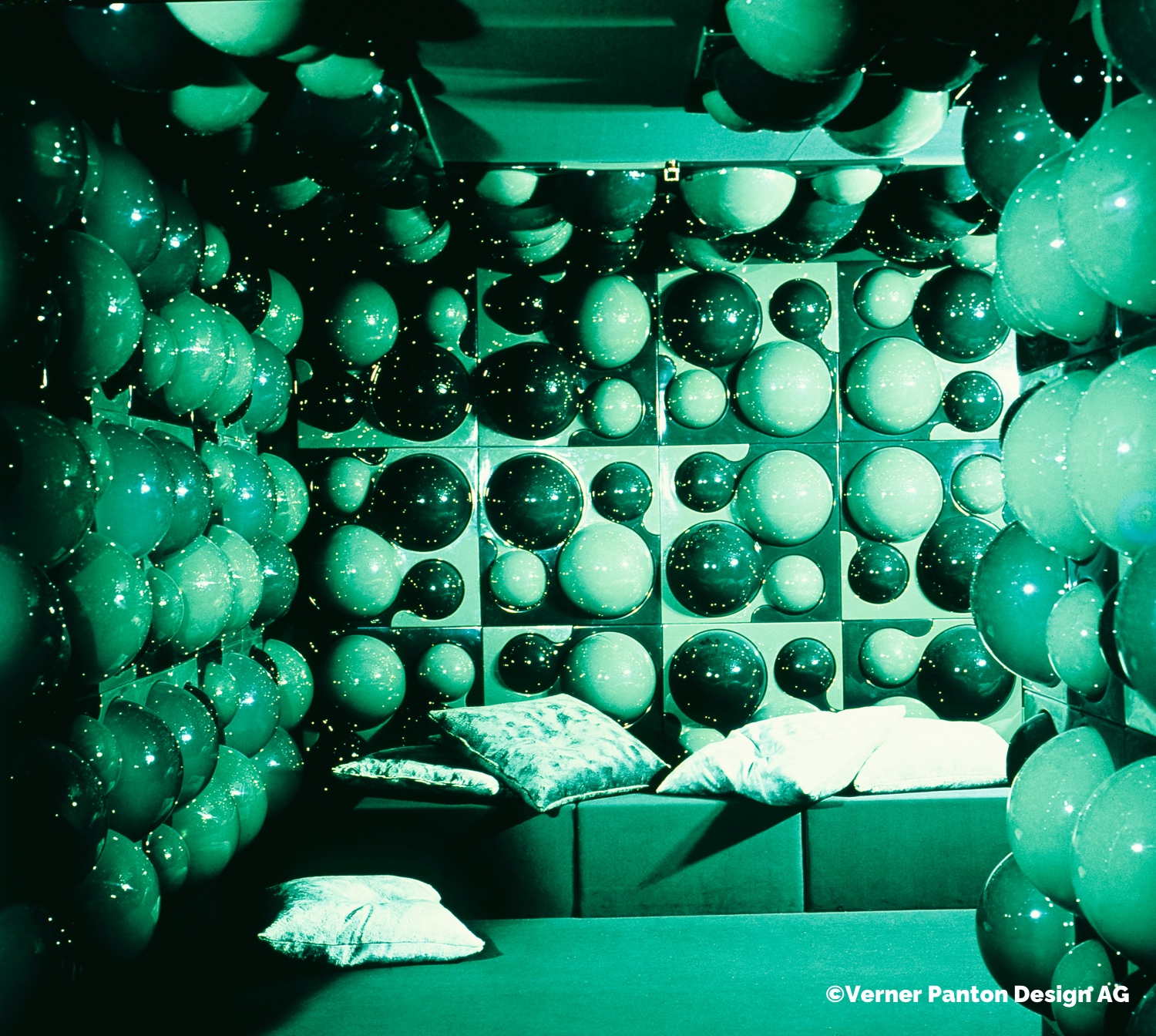

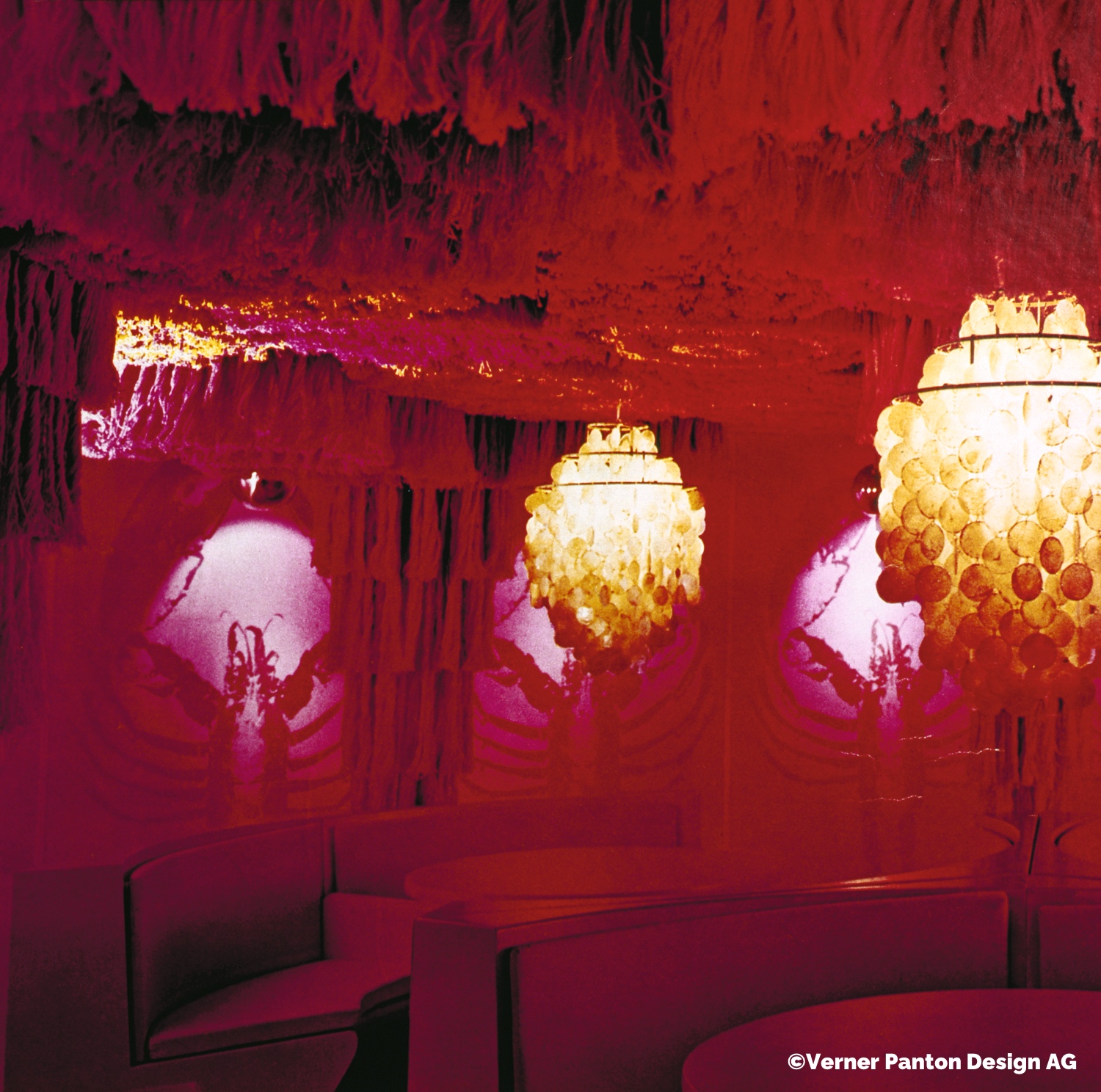

Visiona 0 and II (1968 and 1970)

Verner Panton asks:

should one hang art on the walls, arrange trinkets on shelves and drape rugs across the floors?

or should the entire room be a work of art in which lighting, colours, textiles and furniture are components of a whole?

With the Visiona exhibitions, Panton was given the opportunity to – according to his own statement – realise the most exciting commissions for the German company Bayer. The exhibitions were presented on an excursion steamer, Lorelei, which was moored next to the fair in Cologne Germany, displaying furniture, lamps and textiles that took on added dimensions by growing out of walls and floors. With their interaction of light and colour – augmented by the music of the time – both exhibitions became psychedelic testing grounds for how a future home might be designed (Matz, 1995). With colours embodying his vision for a future home, Panton engaged the sensuous body and the subconscious mind to drown out notions of good taste, thereby creating a feeling of well-being.

Panton’s dream of living with all senses engaged

Verner Panton asks:

why are the sounds reproduced in an apartment always music?

are the sounds of a chicken coop – waves – the wind and many other things not equally beautiful?

Panton dreams of a home where the inhabitants’ eyes, nose, ears, body and mind receive a rich and varied array of impressions. According to him, Danes generally live in very similar homes and often act like their neighbours – and there is no good reason to do so (Goranov, 1998). Combining Panton’s designs with natural and non-man-made sounds from everyday life – such as the sound of chicken coops, rippling waves and whistling winds – creates an active source of well-being.

Panton’s dream of living with all the senses engaged and his ideas for visionary settings full of colour and light were often realised in exhibitions. The Visiona shows in particular were career highlights for Panton in terms of presenting his takes on the home of the future. The installation Light and Colour at Trapholt encapsulated a selection of his oeuvre and design approach just prior to his death in 1998.

The 2021-22 exhibition at Trapholt presents relevant example of Panton’s work accompanied by his own questions, playing directly into his understanding of how we experience well-being in a phenomenological sense. From our present-day vantage point, we see that Panton’s holistic ideas did not have a permanent impact as fully formed totalities; rather, they can be said to have influenced the concept of good taste, as is often the case with radical ideas that are not fully implemented.

This article presents Panton’s views on the culture-bound concept of taste and the biological concept of well-being. Panton sought to bypass good taste in favour of well-being. For him, taste was secondary to well-being and therefore preconditioned by it, and perhaps that is why Panton comes across as different and something of a solitary figure among his fellow designers and architects. In a time of health-crises, where the possibility of social change is present, Panton’s insistence on all things physical and immediate pushes, much like a movement, our social norms in new directions. Thereby, in aesthetic terms, repositioning taste in a position where it is much more conditioned by well-being than it has been for a long time.

Whether or not good taste can also constitute a sense of well-being, Panton points to an extension of the concept that connects aesthetics with health-related life phenomena such as well-being. Taking Panton’s creative process as our starting point, it seems natural to ask whether a health crisis may push us in a direction where we consider totalities and our senses as key factors in our lives.

About the writer

Sara Staunsager, b. 1988, BA in Design History from the University of Southern Denmark and Mag. Art in Aesthetics and Culture from Aarhus University, Denmark, is Curator and Head of Collections at Trapholt Museum of Modern Art and Design. Sara researches design, and her main focus lies on Danish Designers in the 20th century. Significant publications includes: Staunsager, S., Koefoed, L. (2015): Gendered Chairs – The Art of Being a Female Furniture Designer in Passepartout (red.), Women in Art History; Staunsager, S. (2015): An unheralded pioneer in Danish Design by Jens Quistgaard, HEART Museum of Contemporary Art and Staunsager, S. (2018): The Architect’s Cube in Arne Jacobsens Kubeflex, Katrine Stenum (ed.) Trapholt; Staunsager, S. (2018): From Toy to Design Icon – Obsessed with Kay Bojesen’s Monkey in Kay Bojesen – The Joy in Danish Design, Trapholt.

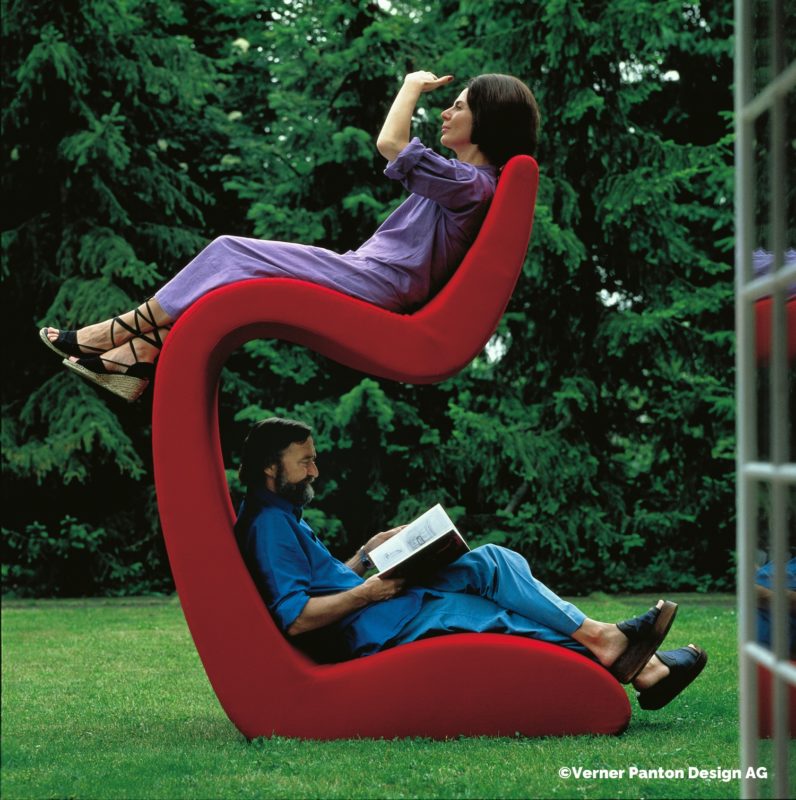

Marianne and Verner Panton in Two Level Seat – in 1973

Sources

Agersted, L. (1969). “I troldmandens værksted” i Femina, nr. 1 januar, s. 30-34.

Birkelund, R. (2013). “Det æstetiske indtryks betydning for sundhed, sygdom og velvære” i Sygdommens rum, Tidskrift for Forskning i Sygdom og Samfund, nr. 18. Afd. For Antropologi og Etnografi, Aarhus Universitet, red.: Risør, Mette Bech m.fl., Højbjerg, s. 13-20.

Blaser, W. (1995). “Verner Panton: Meine Design-Philosophie” i BÜROszene nr. 1-2, s. 28-32.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Distinction – A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Routledge, London.

Erup, B. (1992). “Rødt er så dejligt” i Mad & Bolig, nr. 6 december, s. 88-93.

Fisker, K. (1950). “Den funktionelle tradition – Spredte indtryk af amerikansk arkitektur” i Arkitekten, Månedshæfte 1950, 52. årgang. Arkitektens Forlag, København, red.: Jens Mollerup, Willy Hansen, Finn Juhl, Fl. Teisen og Joh. Pedersen, s. 69-100.

Goranov, C. (1998). “Efter 40 år i Schweiz: Panton bekender kulør” i Nyt fra Danmark.

Hansen, L. Kofoed og Staunsager, S. (2015). “Se min Kropsholder – Kunsten at være kvindelig møbeldesigner” i Passepartout, vol. 19, nr. 36, s. 44-63.

Hartung, M. (1979). “De kritiserer dansk design – Pænt, men kedeligt” i Berlingske Tidende, 2. august.

Helles, V. (1980). “Man sku’ forbyde hvidt!” i Bo Bedre, nr. 4, s. 62-65.

Heidegger, M. (2000). Sproget og Ordet, Hans Reitzels Forlag, 2. udgave, 1. oplag, oversat af Kasper Nefer Olsen, s. 33-54.

Holm, A. (1999). “Festlig frontfigur” i Antik &

Auktion, 1/99, s. 52-56.

Klint, K. (1930). “Om møbeltegning” i Arkitekten, Månedshæfte oktober, s. 193-203.

Lund, M. (2020). “Åbningstalen” i Danske taler: 20 opbyggelige analyser. Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 51-67.

Lund, M. m.fl. (2020). “Officielle taler” i Danske taler: 20 opbyggelige analyser. Aarhus Universitetsforlag, red.:

Lund, M., Madsen, C., Bjerggaard Nielsen, E., Roer, H., og S. Villadsen, L., s. 45-49.

Lykten, M. (2019). Danske lamper – 1920 til nu. København, Strandberg, s. 98.

Matz, T. (1995). “Dansk designer med format: Panton har sat kulør på hele verden” i Kunst &

Antikviteter, april/juni, s. 5-9.

Panton, V. (1991, 2. udg. 1997). Lidt om Farver, Dansk Design Center, København, s. 1-48.

Panton, V. (1992). “Så er det sagt” i Politiken, januar, s. 5.

Panton, V. (1980). “mine damer og herrer –” i Svend Erik Møller: På Wegners tid. Festskrift til Hans J. Wegner 2. april 1989. Poul Kristensens Forlag, Herning, s. 149-154.

Rémy-Jensen, J. (1988). “Hellere fantasi end god smag” i Berlingske, 24. august, sektion: Boligen s. 4.

S.S. (1996). “Den bedste idé kommer i morgen” i Bo Bedre, juni 1996.

Victors, O. (1970). “Den gale dansker i Basel” i Ude og Hjemme, nr. 29 juli.